Online Newsletter Committed to Excellence in the Fields of Mental Health, Addiction, Counseling, Social Work, and Nursing

April 26, 2012

Agent Reduces Autism-like Behaviors in Mice

Press Release • April 25, 2012

Agent Reduces Autism-like Behaviors in Mice

Boosts Sociability, Quells Repetitiveness – NIH Study

National Institutes of Health researchers have reversed behaviors in mice resembling two of the three core symptoms of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). An experimental compound, called GRN-529, increased social interactions and lessened repetitive self-grooming behavior in a strain of mice that normally display such autism-like behaviors, the researchers say.

GRN-529 is a member of a class of agents that inhibit activity of a subtype of receptor protein on brain cells for the chemical messenger glutamate, which are being tested in patients with an autism-related syndrome. Although mouse brain findings often don’t translate to humans, the fact that these compounds are already in clinical trials for an overlapping condition strengthens the case for relevance, according to the researchers.

“Our findings suggest a strategy for developing a single treatment that could target multiple diagnostic symptoms,” explained Jacqueline Crawley, Ph.D., of the NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). “Many cases of autism are caused by mutations in genes that control an ongoing process – the formation and maturation of synapses, the connections between neurons. If defects in these connections are not hard-wired, the core symptoms of autism may be treatable with medications.”

Crawley, Jill Silverman, Ph.D., and colleagues at NIMH and Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development, Groton, CT, report on their discovery April 25th, 2012 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"These new results in mice support NIMH-funded research in humans to create treatments for the core symptoms of autism,” said NIMH director Thomas R. Insel, M.D. “While autism has been often considered only as a disability in need of rehabilitation, we can now address autism as a disorder responding to biomedical treatments." social worker ceus

Crawley’s team followed-up on clues from earlier findings hinting that inhibitors of the receptor, called mGluR5, might reduce ASD symptoms. This class of agents – compounds similar to GRN-529, used in the mouse study – are in clinical trials for patients with the most common form of inherited intellectual and developmental disabilities, Fragile X syndrome, about one third of whom also meet criteria for ASDs.

To test their hunch, the researchers examined effects of GRN-529 in a naturally occurring inbred strain of mice that normally display autism-relevant behaviors. Like children with ASDs, these BTBR mice interact and communicate relatively less with each other and engage in repetitive behaviors – most typically, spending an inordinate amount of time grooming themselves.

Crawley’s team found that BTBR mice injected with GRN-529 showed reduced levels of repetitive self-grooming and spent more time around – and sniffing nose-to-nose with – a strange mouse.

Moreover, GRN-529 almost completely stopped repetitive jumping in another strain of mice.

“These inbred strains of mice are similar, behaviorally, to individuals with autism for whom the responsible genetic factors are unknown, which accounts for about three fourths of people with the disorders,” noted Crawley. “Given the high costs – monetary and emotional – to families, schools, and health care systems, we are hopeful that this line of studies may help meet the need for medications that treat core symptoms.”

Reference:

Silverman JL, Smith DG, Rizzo SJS, Karras MN, Turner SM, Tolu SS, Bryce DK, Smith DL, Fonseca K, Ring RH, Crawley, JN. Negative allosteric modulation of the MGluR5 receptor reduces repetitive behaviors and rescues social deficits in mouse models of autism. April 25, 2012, Science Translational Medicine.

Labels:

autism,

genes,

Social Worker CEUs,

study

April 25, 2012

In a nationally representative survey of 12- to 17-year-old youth and their trauma experiences, 39 percent reported witnessing violence, 17 percent reported physical assault, and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault.

April 2012 Social Media Message

In a nationally representative survey of 12- to 17-year-old youth and their trauma experiences, 39 percent reported witnessing violence, 17 percent reported physical assault, and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault.

With help from families, friends, providers, and other Heroes of Hope, children and youth can be resilient when dealing with trauma. Visit www.samhsa.gov/children to learn more.

When looking at rates of exposure to traumatic events, a nationally representative survey reported that among 12- to 17-year-old youth, 39 percent reported witnessing violence, 17 percent reported physical assault, and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault.1, 2 ceus for social workers

Research has shown that caregivers can buffer the impact of trauma and promote better outcomes for children, even under stressful times, when the following Strengthening Families Protective Factors are present:

•Parental resilience

•Social connections

•Knowledge of parenting and child development

•Concrete support in times of need

•Social and emotional competence of children3

Use these sample messages to share this childhood trauma and resilience data point with your connections on Twitter and Facebook and via email.

Twitter: 39% of 12- to 17-year-old youths have reported witnessing violence, learn more: http://1.usa.gov/Ie4UjT via @samhsagov #HeroesofHope

Facebook: A national survey of 12- to 17-year-old youths found that 17 percent reported physical assault and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault. Learn more about the behavioral health impact of traumatic events on children and youth and pass it on to observe National Children's Mental Health Awareness Day: http://1.usa.gov/Ie4UjT

References:

1. Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R. (2003). Mental health needs of crime victims: Epidemiology and outcomes. Journal of Traumatic Stress.16(2),119–132. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1023/A:1022891005388/abstract .

2.Saunders BE. (2003). Understanding Children Exposed to Violence Toward an Integration of Overlapping Fields. National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center. J Interpers Violence. 18(4) 356-376. Retrieved from http://jiv.sagepub.com/content/18/4/356.short .

3.Horton, C. (2003). Protective factors literature review. Early care and education programs and the prevention of child abuse and neglect. Center for the Study of Social Policy.

Labels:

assault,

ceus for social workers,

child development,

emotional,

violence

The biology behind alcohol-induced blackouts

A person who drinks too much alcohol may be able to perform complicated tasks, such as dancing, carrying on a conversation or even driving a car, but later have no memory of those escapades. These periods of amnesia, commonly known as "blackouts," can last from a few minutes to several hours.

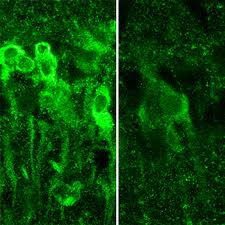

Now, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, neuroscientists have identified the brain cells involved in blackouts and the molecular mechanism that appears to underlie them. They report July 6, 2011, in The Journal of Neuroscience, that exposure to large amounts of alcohol does not necessarily kill brain cells as once was thought. Rather, alcohol interferes with key receptors in the brain, which in turn manufacture steroids that inhibit long-term potentiation (LTP), a process that strengthens the connections between neurons and is crucial to learning and memory.

Better understanding of what occurs when memory formation is inhibited by alcohol exposure could lead to strategies to improve memory.

"The mechanism involves NMDA receptors that transmit glutamate, which carries signals between neurons," says Yukitoshi Izumi, MD, PhD, research professor of psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. "An NMDA receptor is like a double-edged sword because too much activity and too little can be toxic. We've found that exposure to alcohol inhibits some receptors and later activates others, causing neurons to manufacture steroids that inhibit LTP and memory formation." social worker continuing education

Izumi says the various receptors involved in the cascade interfere with synaptic plasticity in the brain's hippocampus, which is known to be important in cognitive function. Just as plastic bends and can be molded into different shapes, synaptic plasticity is a term scientists use to describe the changeable properties of synapses, the sites where nerve cells connect and communicate. LTP is the synaptic mechanism that underlies memory formation.

The brain cells affected by alcohol are found in the hippocampus and other brain structures involved in advanced cognitive functions. Izumi and first author Kazuhiro Tokuda, MD, research instructor of psychiatry, studied slices of the hippocampus from the rat brain.

When they treated hippocampal cells with moderate amounts of alcohol, LTP was unaffected, but exposing the cells to large amounts of alcohol inhibited the memory formation mechanism.

IMAGE:When exposed to large amounts of alcohol, neurons in the hippocampus produce steroids (shown in bright green, at left), which inhibit the formation of memory.

"It takes a lot of alcohol to block LTP and memory," says senior investigator Charles F. Zorumski, MD, the Samuel B. Guze Professor and head of the Department of Psychiatry. "But the mechanism isn't straightforward. The alcohol triggers these receptors to behave in seemingly contradictory ways, and that's what actually blocks the neural signals that create memories. It also may explain why individuals who get highly intoxicated don't remember what they did the night before."

But not all NMDA receptors are blocked by alcohol. Instead, their activity is cut roughly in half.

"The exposure to alcohol blocks some NMDA receptors and activates others, which then trigger the neuron to manufacture these steroids," Zorumski says.

The scientists point out that alcohol isn't causing blackouts by killing neurons. Instead, the steroids interfere with synaptic plasticity to impair LTP and memory formation.

"Alcohol isn't damaging the cells in any way that we can detect," Zorumski says. "As a matter of fact, even at the high levels we used here, we don't see any changes in how the brain cells communicate. You still process information. You're not anesthetized. You haven't passed out. But you're not forming new memories."

Stress on the hippocampal cells also can block memory formation. So can consumption of other drugs. When combined, alcohol and certain other drugs are much more likely to cause blackouts than either substance alone.

The researchers found that if they could block the manufacture of steroids by neurons, they also could preserve LTP in the rat hippocampus. And they did that with drugs called 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. These include finasteride and dutasteride, which are commonly prescribed to reduce a man's enlarged prostate gland. In the brain, however, those substances seem to preserve memory.

"We would expect there may be some differences in the effects of alcohol on patients taking these drugs," Izumi says. "Perhaps men taking the drugs would be less likely to experience intoxication blackouts."

The researchers plan to study 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors to see how easily they get into the brain and to determine whether those drugs, or similar substances, might someday play a role in preserving memory.

Tokuda K, Izumi Y, Zorumski CF. Ethanol enhances neurosteroidogenesis in hippocampal pyramidal neurons by paradoxical NMDA receptor activation, The Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 31(27), pp. 9905-9909. July 6, 2011.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by the Bantley Foundation.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Labels:

induced,

memory,

neurons,

Social Worker Continuing Education

April 24, 2012

Stress about wife's breast cancer can harm a man's health

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Caring for a wife with breast cancer can have a measurable negative effect on men's health, even years after the cancer diagnosis and completion of treatment, according to recent research.

Men who reported the highest levels of stress in relation to their wives' cancer were at the highest risk for physical symptoms and weaker immune responses, the study showed.

The researchers sought to determine the health effects of a recurrence of breast cancer on patients' male caregivers, but found that how stressed the men were about the cancer had a bigger influence on their health than did the current status of their wives' disease.

The findings imply that clinicians caring for breast cancer patients could help their patients by considering the caregivers' health as well, the researchers say.

This care could include screening caregivers for stress symptoms and encouraging them to participate in stress management, relaxation or other self-care activities, said Sharla Wells-Di Gregorio, lead author of the study and assistant professor of psychiatry and psychology at Ohio State University.

"If you care for the caregiver, your patient gets better care, too," said Kristen Carpenter, a postdoctoral researcher in psychology at Ohio State and a study co-author LSW Continuing Education

The research is published in a recent issue of the journal Brain, Behavior and Immunity.

Thirty-two men participated in the study, including 16 whose wives had experienced a breast cancer recurrence an average of eight months before the study began and approximately five years after the initial cancer diagnosis. These men were matched with 16 men whose wives' cancers were similar, but who remained disease-free about six years after the initial diagnosis.

The participants completed several questionnaires measuring levels of psychological stress related to their wives' cancers, physical symptoms related to stress, and the degree to which fatigue interfered with their daily functioning. Researchers tested their immune function by analyzing white-blood-cell activation in response to three different types of antigens, or substances that prompt the body to produce an immune response.

The men's median age was 58 years and they had been married, on average, for 26 years. Almost all of the participants were white.

In general, the men whose wives had experienced a recurrence of cancer reported higher levels of stress, greater interference from fatigue and more physical symptoms, such as headaches and abdominal pain, than did men whose wives had remained disease-free.

The subjective stress assessment used in the study, called the Impact of Events Scale, measures intrusive experiences and thoughts, as well as attempts to avoid people and places that serve as painful reminders. The scale produces a score between 0 and 75; in this case, the higher the score, the more stressed the men were in relation to their wives' cancer.

Overall, the men in the study produced an average score of 17.59. Men whose wives' cancer had recurred scored 26.25 as a group, and men whose wives were disease-free scored 8.94. According to the scale, scores above nine suggest a likely effect from the events, and scores between 26 and 43 indicate an event has had a powerful effect on a person's stress level. Scores over 33 suggest clinically significant distress.

"The scores reported here are quite high, substantially higher than we see in our cancer patient samples outside the first year," Carpenter said. "Guilt, depression, fear of loss – all of those things are stressful. And this is not an acute stressor that lasts a few weeks. It's a chronic stress that lasts for years."

The participants also reported, on average, a total of approximately seven stress-related physical symptoms. Men with wives with recurrent cancer reported nine symptoms, on average, and those whose wives were disease-free reported fewer than five symptoms, on average. These symptoms varied, but included headaches, gastrointestinal problems, coughing and nausea.

When the analysis took into consideration the impact of men's perceived stress in relation to their wives' cancer, higher stress was associated with compromised immune function: Specifically, men with the highest scores on the stress scale also showed the lowest immune responses to two of the three antigens. Previous research has suggested that people with an impaired immune response are more susceptible to infection and might not respond well to vaccines.

"Caregivers are called hidden patients because when they go in for appointments with their spouses, very few people ask how the caregiver is doing," said Wells-Di Gregorio, who works in Ohio State's Center for Palliative Care. "These men are experiencing significant distress and physical complaints, but often do not seek medical care for themselves due to their focus on their wives' illness."

In these men undergoing chronic stress, the researchers said that it remains unclear whether the immune dysregulation causes more physical symptoms, or stress causes the symptoms and the impaired immune response.

Wells-Di Gregorio noted that the stress effect might have been even more pronounced than what they observed because disease-free spouses were more reluctant to participate in the study.

"We found that many were not willing to participate because they said they didn't want to think about cancer again," she said.

This research was supported by the Ann and Herbert Siegel American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship, the Longaberger Company-American Cancer Society Grant for Breast Cancer Research, the U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity Grants, the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Co-authors included Caroline Dorfman and Hae-Chung Yang of Ohio State's Department of Psychology; Laura Simonelli of the Christiana Care Health System; and William Carson III of Ohio State's Department of Surgery and Comprehensive Cancer Center

Labels:

cancer,

health,

lsw continuing education,

stress

April 23, 2012

Gatekeeper of brain steroid signals boosts emotional resilience to stress

PHILADELPHIA - A cellular protein called HDAC6, newly characterized as a gatekeeper of steroid biology in the brain, may provide a novel target for treating and preventing stress-linked disorders, such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), according to research from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Glucocorticoids are natural steroids secreted by the body during stress. A small amount of these hormones helps with normal brain function, but their excess is a precipitating factor for stress-related disorders.

Glucocorticoids exert their effects on mood by acting on receptors in the nucleus of emotion–regulating neurons, such as those producing the neurotransmitter serotonin. For years, researchers have searched for ways to prevent deleterious effects of stress by blocking glucocorticoids in neurons. However, this has proved difficult to do without simultaneously interfering with other functions of these hormones, such as the regulation of immune function and energy metabolism.

In a recent Journal of Neuroscience paper, the lab of Olivier Berton, PhD, assistant professor of Psychiatry, shows how a regulator of glucocorticoid receptors may provide a path towards resilience to stress by modulating glucocorticoid signaling in the brain. The protein HDAC6, which is particularly enriched in serotonin pathways, as well as in other mood-regulatory regions in both mice and humans, is ideally distributed in the brain to mediate the effect of glucocorticoids on mood and emotions. HDAC6 likely does this by controlling the interactions between glucocorticoid receptors and hormones in these serotonin circuits ceus for social workers

Experiments that first alerted Berton and colleagues to a peculiar role of HDAC6 in stress adaptation came from an approach that reproduces certain clinical features of traumatic stress and depression in mice. The animals are exposed to brief bouts of aggression from trained "bully" mice. In most aggression-exposed mice this experience leads to the development of a lasting form of social aversion that can be treated by chronic administration of antidepressants.

In contrast, a portion of mice exposed to chronic aggression consistently express spontaneous resilience to the stress and do not develop any symptoms. By comparing gene expression in the brains of spontaneously resilient and vulnerable mice, Berton and colleagues discovered that reducing HDAC6 expression is a hallmark of naturally resilient animals. While aggression also caused severe changes in the shape of serotonin neurons and their capacity to transmit electrical signals in vulnerable mice, stress-resilient mice, in contrast, escaped most of these neurobiological changes.

To better understand the link between HDAC6 and the development of stress resilience, Berton and colleagues devised a genetic approach to directly manipulate HDAC6 levels in neurons: Deletion of HDAC6 in serotonin neurons -- the densest HDAC6-expressing cell group in the mouse brain -- dramatically reduced social and anxiety symptoms in mice exposed to bullies and also fully prevented neurobiological changes due to stress, fully mimicking a resilient phenotype.

Using biochemical assays, Berton's team showed it is by promoting reversible chemical changes onto a heat shock chaperone protein, Hsp90, that HDAC6 deletion is able to literally switch off the effects of glucocorticoid hormones on social and anxiety behaviors.

Chaperones are proteins that help with the folding or unfolding and the assembly or disassembly of protein complexes. The way in which glucocorticoid receptor chaperoning and stress are linked is not well understood. Yet, genetic variations in certain components of the glucocorticoid receptor chaperone complex have been associated with the development of stress-related disorders and individual variability in therapeutic responses to antidepressants.

"We provide pharmacological and genetic evidence indicating that HDAC6 controls certain aspects of Hsp90 structure and function in the brain, and thereby modulates protein interactions, as well as hormone- and stress-induced glucocorticoid receptor signaling and behavior," explains Berton.

Together, these results identify HDAC6 as a possible stress vulnerability biomarker and point to pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 as a potential new strategy for antidepressant interventions through regulation of Hsp90 in glucocorticoid signaling in serotonin neurons.

Co-first-authors are Julie Espallergues and Sarah L. Teegarden, along with Avin Veerakumar, Janette Boulden, Collin Challis, Jeanine Jochems, Michael Chan, Tess Petersen, Chang-Gyu Hahn, Irwin Lucki, and Sheryl G. Beck, all from Penn. Other authors are Evan Deneris, from Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, and Patrick Matthias, Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, Basel, Switzerland.

This work was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health grants MH087581 and MH0754047 and grants from the International Mental Health Research Organization and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine is currently ranked #2 in U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $479.3 million awarded in the 2011 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top 10 hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; and Pennsylvania Hospital - the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Penn Medicine also includes additional patient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2011, Penn Medicine provided $854 million to benefit our community.

Labels:

brain,

ceus for social workers,

emotion,

stress

April 22, 2012

Phobia's effect on perception of feared object allows fear to persist

COLUMBUS, Ohio – The more afraid a person is of a spider, the bigger that individual perceives the spider to be, new research suggests.

In the context of a fear of spiders, this warped perception doesn't necessarily interfere with daily living. But for individuals who are afraid of needles, for example, the conviction that needles are larger than they really are could lead people who fear injections to avoid getting the health care they need.

A better understanding of how a phobia affects the perception of feared objects can help clinicians design more effective treatments for people who seek to overcome their fears, according to the researchers.

In this study, participants who feared spiders were asked to undergo five encounters with live spiders – tarantulas, in fact – and then provide size estimates of the spiders after those encounters ended. The more afraid the participants said they were of the spiders, the larger they estimated the spiders had been.

"If one is afraid of spiders, and by virtue of being afraid of spiders one tends to perceive spiders as bigger than they really are, that may feed the fear, foster that fear, and make it difficult to overcome," said Michael Vasey, professor of psychology at Ohio State University and lead author of the study.

"When it comes to phobias, it's all about avoidance as a primary means of keeping oneself safe. As long as you avoid, you can't discover that you're wrong. And you're stuck. So to the extent that perceiving spiders as bigger than they really are fosters fear and avoidance, it then potentially is part of this cycle that feeds the phobia that leads to its persistence continuing education for social workers

"We're trying to understand why phobias persist so we can better target treatments to change those reasons they persist."

The study is published in a recent issue of the Journal of Anxiety Disorders.

The researchers recruited 57 people who self-identified as having a spider phobia. Each participant then interacted at specific time points over a period of eight weeks with five different varieties of tarantulas varying in size from about 1 to 6 inches long.

The spiders were contained in an uncovered glass tank. Participants began their encounters 12 feet from the tank and were asked to approach the spider. Once they were standing next to the tank, they were asked to guide the spider around the tank by touching it with an 8-inch probe, and later with a shorter probe.

Throughout these encounters, researchers asked participants to report how afraid they were feeling on a scale of 0-100 according to an index of subjective units of distress. After the encounters, participants completed additional self-report measures of their specific fear of spiders, any panic symptoms they experienced during the encounters with the spiders, and thoughts about fear reduction and future spider encounters.

Finally, the research participants estimated the size of the spiders – while no longer being able to see them – by drawing a single line on an index card indicating the length of the spider from the tips of its front legs to the tips of its back legs.

An analysis of the results showed that higher average peak ratings of distress during the spider encounters were associated with estimates that the spiders were larger than they really were. Similar positive associations were seen between over-estimates of spider size and participants' higher average peak levels of anxiety, higher average numbers of panic symptoms and overall spider fear. These findings have been supported in later studies with broader samples of people with varying levels of fear of spiders.

"It would appear from that result that fear is driving or altering the perception of the feared object, in this case a spider," said Vasey, also the director of research for the psychology department's Anxiety and Stress Disorders Clinic. "We already knew fear and anxiety alter thoughts about the feared thing. For example, the feared outcome is interpreted as being more likely than it really is. But this study shows that even perception is altered by fear. In this case, the feared spider is seen as being bigger. And that may serve as a maintaining factor for the fear."

The approach tasks with the spiders are a classic example of exposure therapy, a common treatment for people with phobias. Though this therapy is known to be effective, scientists still do not fully understand why it works. And for some, the effects don't last – but it is difficult to predict who will have a relapse of fear, Vasey said.

He and colleagues are studying these biased perceptions as well as attitudes with hopes that the new knowledge will enhance treatment for people with various phobias. The work suggests that fear not only alters one's perception of the feared thing, but also can influence a person's automatic attitude toward an object. Those who have developed an automatic negative attitude toward a feared object might have a harder time overcoming their fear.

Though individuals with arachnophobia are unlikely to seek treatment, the use of spiders in this research was a convenient way to study the complex effects of fear on visual perception and how those effects might cause fear to persist, Vasey noted.

"Ultimately, we are interested in identifying predictors of relapse so we can better measure when a person is done with treatment," he said.

This work is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Co-authors include Michael Vilensky, Jacqueline Heath, Casaundra Harbaugh, Adam Buffington and Vasey's principal collaborator, Russell Fazio, all of Ohio State's Department of Psychology.

April 18, 2012

Genetic manipulation boosts growth of brain cells linked to learning, enhances antidepressants

DALLAS -- UT Southwestern Medical Center investigators have identified a genetic manipulation that increases the development of neurons in the brain during aging and enhances the effect of antidepressant drugs.

The research finds that deleting the Nf1 gene in mice results in long-lasting improvements in neurogenesis, which in turn makes those in the test group more sensitive to the effects of antidepressants.

"The significant implication of this work is that enhancing neurogenesis sensitizes mice to antidepressants – meaning they needed lower doses of the drugs to affect 'mood' – and also appears to have anti-depressive and anti-anxiety effects of its own that continue over time," said Dr. Luis Parada, director of the Kent Waldrep Center for Basic Research on Nerve Growth and Regeneration and senior author of the study published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

Just as in people, mice produce new neurons throughout adulthood, although the rate declines with age and stress, said Dr. Parada, chairman of developmental biology at UT Southwestern. Studies have shown that learning, exercise, electroconvulsive therapy and some antidepressants can increase neurogenesis. The steps in the process are well known but the cellular mechanisms behind those steps are not.

"In neurogenesis, stem cells in the brain's hippocampus give rise to neuronal precursor cells that eventually become young neurons, which continue on to become full-fledged neurons that integrate into the brain's synapses," said Dr. Parada, an elected member of the prestigious National Academy of Sciences, its Institute of Medicine, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The researchers used a sophisticated process to delete the gene that codes for the Nf1 protein only in the brains of mice, while production in other tissues continued normally. After showing that mice lacking Nf1 protein in the brain had greater neurogenesis than controls, the researchers administered behavioral tests designed to mimic situations that would spark a subdued mood or anxiety, such as observing grooming behavior in response to a small splash of sugar water.

The researchers found that the test group mice formed more neurons over time compared to controls, and that young mice lacking the Nf1 protein required much lower amounts of anti-depressants to counteract the effects of stress. Behavioral differences between the groups persisted at three months, six months and nine months. "Older mice lacking the protein responded as if they had been taking antidepressants all their lives," said Dr. Parada.

"In summary, this work suggests that activating neural precursor cells could directly improve depression- and anxiety-like behaviors, and it provides a proof-of-principle regarding the feasibility of regulating behavior via direct manipulation of adult neurogenesis," Dr. Parada said.

Dr. Parada's laboratory has published a series of studies that link the Nf1 gene – best known for mutations that cause tumors to grow around nerves – to wide-ranging effects in several major tissues. For instance, in one study researchers identified ways that the body's immune system promotes the growth of tumors, and in another study, they described how loss of the Nf1 protein in the circulatory system leads to hypertension and congenital heart disease social worker ceus

The current study's lead author is former graduate student Dr. Yun Li, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Other co-authors include Yanjiao Li, a research associate of developmental biology, Dr. Renée McKay, assistant professor of developmental biology, both of UT Southwestern, and Dr. Dieter Riethmacher of the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Parada is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

This news release is available on our World Wide Web home page at www.utsouthwestern.edu/home/news/index.html

To automatically receive news releases from UT Southwestern via email, subscribe at www.utsouthwestern.edu/receivenews

Labels:

brain,

brain cells,

gene,

Social Worker CEU,

Social Worker CEUs

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)