Online Newsletter Committed to Excellence in the Fields of Mental Health, Addiction, Counseling, Social Work, and Nursing

April 30, 2012

LA BioMed researchers remain at the forefront of mental health initiatives

The month of May recognized as Mental Health Awareness Month

LOS ANGELES (April 30, 2012) – With the month of May recognized nationally as Mental Health Awareness Month, the physician-researchers at the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (LA BioMed) continue to be at the forefront of mental health initiatives, engaging in clinical trials to help find therapies and treatments for individuals who suffer from mood and anxiety disorders. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), mental health concerns affect 1 in 10 Americans today, but fewer than 25 percent of people with a diagnosable mental disorder seek treatment.

Ira Lesser, M.D., is a principal investigator at LA BioMed and Chair, Department of Psychiatry, at Harbor-UCLA. At LA BioMed, he has led a number of clinical trials on mood and anxiety disorders, including the largest ever conducted on depression – Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) – a study funded by the NIMH. LA BioMed was one of 41 clinical sites participating, enrolling the greatest number of individuals and was the highest primary care enrolling site in the country.

"With a growing number of individuals being diagnosed with a mental health disorder, it's imperative that we educate these individuals as to the options available to them, and also encourage them to seek treatment," said Dr. Lesser. "At LA BioMed, we are working to develop treatments and therapies that will not only help to cure but also help individuals cope with their existing conditions in the long term."

In addition to STAR*D, Dr. Lesser and his staff (Karl Burgoyne, M.D., Benjamin Furst, M.D., Deborah Flores, M.D.) are working on other clinical trials including Biomarkers for Rapid Identification of Treatment Effectiveness in Major Depression (BRITE) and Biomarkers for Outcomes in Late-Life Depression (BOLD).

Working alongside Dr. Lesser is LA BioMed investigator Michele Berk, Ph.D., who is directing a multi-site, randomized clinical trial that tests the effects of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) on teenagers who have attempted suicide or engaged in self-harm behaviors, such as cutting. Suicide now ranks as the third leading cause of death in the U.S. among youth ages 10-19. DBT has been shown to be effective in reducing suicidal behavior in adults with depression and personality disorders. Sponsored by the NIMH, this study is the first such clinical trial in the U.S. to test the effectiveness of DBT in adolescents.

John W. Tsuang, M.D., in conjunction with Steven J. Shoptaw, Ph.D., from the UCLA Department of Family Medicine, is spearheading a Phase I clinical safety trial that for the first time examines the effects of Ibudilast when administered with metamphetamine (MA), an addictive stimulant that is closely related to amphetamine. Funded by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), this study will help to determine the effects of Ibudilast - combined with relevant doses of MA - on heart rate and blood pressure, and whether or not Ibudilast alters the way in which the body absorbs, distributes, and metabolizes MA. The development of one or more medications to reduce MA abuse, when implemented with evidence-based behavioral and counseling interventions, would have obvious public health significance. Dr. Tsuang is hoping that following the initial safety trial, physicians will be able to utilize Ibudilast in treating patients with MA dependence to help them improve memory and reduce the damage done to their central nervous system due to MA abuse social worker continuing education

About LA BioMed

Founded in 1952, LA BioMed is one of the country's leading nonprofit independent biomedical research institutes. It has approximately 100 principal researchers conducting studies into improved treatments and cures for cancer, inherited diseases, infectious diseases, illnesses caused by environmental factors and more. It also educates young scientists and provides community services, including prenatal counseling and childhood nutrition programs. LA BioMed is academically affiliated with the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and located on the campus of Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. For more information, please visit www.LABioMed.org

April 29, 2012

Dual medications for depression increases costs, side effects with no benefit to patients

Taking two medications for depression does not hasten recovery from the condition that affects 19 million Americans each year, researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have found in a national study.

"Clinicians should not rush to prescribe combinations of antidepressant medications as first-line treatment for patients with major depressive disorder," said Dr. Madhukar H. Trivedi, professor of psychiatry and chief of the division of mood disorders at UT Southwestern and principal investigator of the study, which is available online today and is scheduled for publication in an upcoming issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry.

"The clinical implications are very clear – the extra cost and burden of two medications is not worthwhile as a first treatment step," he said.

In the Combining Medication to Enhance Depression Outcomes, or CO-MED, study, researchers at 15 sites across the country studied 665 patients ages 18 to 75 with major depressive disorder. Three treatment groups were formed and prescribed antidepressant medications already approved by the Food and Drug Administration. One group received escitalopram (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, or SSRI) and a placebo; the second group received the same SSRI paired with bupropion (a non-tricyclic antidepressant); and a third group took different antidepressants: venlafaxine (a tetracyclic antidepressant) and mirtazapine (a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor). The study was conducted from March 2008 through February 2009 LSW Continuing Education

After 12 weeks of treatment, remission and response rates were similar across the three groups: 39 percent, 39 percent and 38 percent, respectively, for remission, and about 52 percent in all three groups for response. After seven months of treatment, remission and response rates across the three groups remained similar, but side effects were more frequent in the third group.

Only about 33 percent of depressed patients go into remission in the first 12 weeks of treatment with antidepressant medication, as Dr. Trivedi and colleagues previously reported from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression, or STAR*D, study. STAR*D was the largest study ever undertaken on the treatment of major depressive disorder and is considered a benchmark in the field of depression research. That six-year, $33 million study initially included more than 4,000 patients from sites across the country. Dr. Trivedi was a co-principal investigator of STAR*D.

The next step, Dr. Trivedi said, is to study biological markers of depression to see if researchers can predict response to antidepressant medication and, thus, improve overall outcomes.

###

Other UT Southwestern researchers involved in the study were Drs. Benji Kurian and David Morris, assistant professors of psychiatry; Dr. Diane Warden, associate professor of psychiatry; and Dr. Mustafa Husain, professor of psychiatry, internal medicine, and neurology and neurotherapeutics. Former UT Southwestern professor Dr. A. John Rush, now with the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore, and researchers from the University of Pittsburgh; Massachusetts General Hospital; Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; the University of California, Los Angeles; Vanderbilt University; Harbor-UCLA Medical Center; Virginia Commonwealth University; and Columbia University Medical Center also contributed.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Organon and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals provided the medications.

Visit http://www.utsouthwestern.org/neurosciences to learn more about UT Southwestern's clinical services in neurosciences, including psychiatry.

This news release is available on our World Wide Web home page at www.utsouthwestern.edu/home/news/index.html

To automatically receive news releases from UT Southwestern via email, subscribe at www.utsouthwestern.edu/receivenews

April 27, 2012

Most Children with Rapidly Shifting Moods Don’t Have Bipolar Disorder

Relatively few children with rapidly shifting moods and high energy have bipolar disorder, though such symptoms are commonly associated with the disorder. Instead, most of these children have other types of mental disorders, according to an NIMH-funded study published online ahead of print in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry on October 5, 2010.

Background

Some parents who take their child to a mental health clinic for assessment report that the child has rapid swings between emotions (usually anger, elation, and sadness) coupled with extremely high energy levels. Some researchers suggest that this is how mania—an important component of bipolar disorder—appears in children. How mania and bipolar disorder are defined in children is important because rapid mood swings and high energy are common among youth.

Furthermore, many experts believe that overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder in youth may play a role in the increasing numbers of children being diagnosed with and treated for bipolar disorder. In choosing proper treatment, it is important to know whether children with rapid mood swings and high energy have an early or mild form of bipolar disorder, or instead have a different mental disorder CADC I & II Continuing Education

In the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) study, Robert Findling, M.D., of Case Western Reserve University, and colleagues assessed 707 children, ages 6-12, who were referred for mental health treatment. Of the participants, 621 were rated as having rapid swings between emotions and high energy levels, described as "elevated symptoms of mania" (ESM-positive). Parents of the other 86 children did not report rapid mood swings. These participants were deemed ESM-negative.

Results of the Study

At baseline, all but 14 participants had at least one mental disorder, and many had two or more. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was the most frequent diagnosis, affecting roughly 76 percent in both the ESM-positive and ESM-negative groups. However, only 39 percent were receiving treatment with a stimulant, the most common medication treatment for ADHD, at the start of the study.

Only 11 percent of those with rapid mood swings and high energy (69 out of 621) and 6 percent of those without these symptoms (5 out of 86) had bipolar disorder, meaning that only this small percentage had ever experienced a manic episode, as defined by the current diagnostic system. Of the children with rapid mood swings and high energy, another 12 percent (75 children) had a form of bipolar disorder that includes much shorter manic episodes.

Compared to children without rapid mood swings and high energy, those with these symptoms:

Reported more symptoms of depression, anxiety, manic symptoms, and symptoms of ADHD

Had lower functioning at home, school, or with peers

Were more likely to have a disruptive behavior disorder (oppositional defiant disorder and/or conduct disorder).

Significance

Given that 75 percent of ESM-positive youth did not meet the diagnostic criteria for any bipolar disorder, the researchers suggest that bipolar disorder may not be common among children who experience rapid swings between emotions and high energy levels. Nevertheless, children with these symptoms experience significant impairments due to mood and behavior problems.

The researchers also noted that ESM-positive and ESM-negative youth were prescribed psychotropic medications—including antipsychotics—at similar rates. Further study may provide insight into how serious mental illnesses should be treated in children.

What's Next

The study participants will be re-assessed every 6 months for up to 5 years, allowing the LAMS researchers to determine which children with rapid mood swings and high energy develop bipolar disorder later in life. Such research may inform efforts to identify early markers or predictors of the illness as well as possible protective factors.

Reference

Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, Fristad MA, Birmaher B, Kowatch RA, Arnold E, Frazier TW, Axelson D, Ryan N, Demeter CA, Gill MK, Fields B, Depew J, Kennedy SM, Marsh L, Rowles BM, Horwitz SM. Characteristics of Children With Elevated Symptoms of Mania: The Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) Study. J Clin Psychiatr. Epub 2010 Oct 5.

April 26, 2012

Agent Reduces Autism-like Behaviors in Mice

Press Release • April 25, 2012

Agent Reduces Autism-like Behaviors in Mice

Boosts Sociability, Quells Repetitiveness – NIH Study

National Institutes of Health researchers have reversed behaviors in mice resembling two of the three core symptoms of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). An experimental compound, called GRN-529, increased social interactions and lessened repetitive self-grooming behavior in a strain of mice that normally display such autism-like behaviors, the researchers say.

GRN-529 is a member of a class of agents that inhibit activity of a subtype of receptor protein on brain cells for the chemical messenger glutamate, which are being tested in patients with an autism-related syndrome. Although mouse brain findings often don’t translate to humans, the fact that these compounds are already in clinical trials for an overlapping condition strengthens the case for relevance, according to the researchers.

“Our findings suggest a strategy for developing a single treatment that could target multiple diagnostic symptoms,” explained Jacqueline Crawley, Ph.D., of the NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). “Many cases of autism are caused by mutations in genes that control an ongoing process – the formation and maturation of synapses, the connections between neurons. If defects in these connections are not hard-wired, the core symptoms of autism may be treatable with medications.”

Crawley, Jill Silverman, Ph.D., and colleagues at NIMH and Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development, Groton, CT, report on their discovery April 25th, 2012 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"These new results in mice support NIMH-funded research in humans to create treatments for the core symptoms of autism,” said NIMH director Thomas R. Insel, M.D. “While autism has been often considered only as a disability in need of rehabilitation, we can now address autism as a disorder responding to biomedical treatments." social worker ceus

Crawley’s team followed-up on clues from earlier findings hinting that inhibitors of the receptor, called mGluR5, might reduce ASD symptoms. This class of agents – compounds similar to GRN-529, used in the mouse study – are in clinical trials for patients with the most common form of inherited intellectual and developmental disabilities, Fragile X syndrome, about one third of whom also meet criteria for ASDs.

To test their hunch, the researchers examined effects of GRN-529 in a naturally occurring inbred strain of mice that normally display autism-relevant behaviors. Like children with ASDs, these BTBR mice interact and communicate relatively less with each other and engage in repetitive behaviors – most typically, spending an inordinate amount of time grooming themselves.

Crawley’s team found that BTBR mice injected with GRN-529 showed reduced levels of repetitive self-grooming and spent more time around – and sniffing nose-to-nose with – a strange mouse.

Moreover, GRN-529 almost completely stopped repetitive jumping in another strain of mice.

“These inbred strains of mice are similar, behaviorally, to individuals with autism for whom the responsible genetic factors are unknown, which accounts for about three fourths of people with the disorders,” noted Crawley. “Given the high costs – monetary and emotional – to families, schools, and health care systems, we are hopeful that this line of studies may help meet the need for medications that treat core symptoms.”

Reference:

Silverman JL, Smith DG, Rizzo SJS, Karras MN, Turner SM, Tolu SS, Bryce DK, Smith DL, Fonseca K, Ring RH, Crawley, JN. Negative allosteric modulation of the MGluR5 receptor reduces repetitive behaviors and rescues social deficits in mouse models of autism. April 25, 2012, Science Translational Medicine.

Labels:

autism,

genes,

Social Worker CEUs,

study

April 25, 2012

In a nationally representative survey of 12- to 17-year-old youth and their trauma experiences, 39 percent reported witnessing violence, 17 percent reported physical assault, and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault.

April 2012 Social Media Message

In a nationally representative survey of 12- to 17-year-old youth and their trauma experiences, 39 percent reported witnessing violence, 17 percent reported physical assault, and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault.

With help from families, friends, providers, and other Heroes of Hope, children and youth can be resilient when dealing with trauma. Visit www.samhsa.gov/children to learn more.

When looking at rates of exposure to traumatic events, a nationally representative survey reported that among 12- to 17-year-old youth, 39 percent reported witnessing violence, 17 percent reported physical assault, and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault.1, 2 ceus for social workers

Research has shown that caregivers can buffer the impact of trauma and promote better outcomes for children, even under stressful times, when the following Strengthening Families Protective Factors are present:

•Parental resilience

•Social connections

•Knowledge of parenting and child development

•Concrete support in times of need

•Social and emotional competence of children3

Use these sample messages to share this childhood trauma and resilience data point with your connections on Twitter and Facebook and via email.

Twitter: 39% of 12- to 17-year-old youths have reported witnessing violence, learn more: http://1.usa.gov/Ie4UjT via @samhsagov #HeroesofHope

Facebook: A national survey of 12- to 17-year-old youths found that 17 percent reported physical assault and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault. Learn more about the behavioral health impact of traumatic events on children and youth and pass it on to observe National Children's Mental Health Awareness Day: http://1.usa.gov/Ie4UjT

References:

1. Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R. (2003). Mental health needs of crime victims: Epidemiology and outcomes. Journal of Traumatic Stress.16(2),119–132. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1023/A:1022891005388/abstract .

2.Saunders BE. (2003). Understanding Children Exposed to Violence Toward an Integration of Overlapping Fields. National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center. J Interpers Violence. 18(4) 356-376. Retrieved from http://jiv.sagepub.com/content/18/4/356.short .

3.Horton, C. (2003). Protective factors literature review. Early care and education programs and the prevention of child abuse and neglect. Center for the Study of Social Policy.

Labels:

assault,

ceus for social workers,

child development,

emotional,

violence

The biology behind alcohol-induced blackouts

A person who drinks too much alcohol may be able to perform complicated tasks, such as dancing, carrying on a conversation or even driving a car, but later have no memory of those escapades. These periods of amnesia, commonly known as "blackouts," can last from a few minutes to several hours.

Now, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, neuroscientists have identified the brain cells involved in blackouts and the molecular mechanism that appears to underlie them. They report July 6, 2011, in The Journal of Neuroscience, that exposure to large amounts of alcohol does not necessarily kill brain cells as once was thought. Rather, alcohol interferes with key receptors in the brain, which in turn manufacture steroids that inhibit long-term potentiation (LTP), a process that strengthens the connections between neurons and is crucial to learning and memory.

Better understanding of what occurs when memory formation is inhibited by alcohol exposure could lead to strategies to improve memory.

"The mechanism involves NMDA receptors that transmit glutamate, which carries signals between neurons," says Yukitoshi Izumi, MD, PhD, research professor of psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. "An NMDA receptor is like a double-edged sword because too much activity and too little can be toxic. We've found that exposure to alcohol inhibits some receptors and later activates others, causing neurons to manufacture steroids that inhibit LTP and memory formation." social worker continuing education

Izumi says the various receptors involved in the cascade interfere with synaptic plasticity in the brain's hippocampus, which is known to be important in cognitive function. Just as plastic bends and can be molded into different shapes, synaptic plasticity is a term scientists use to describe the changeable properties of synapses, the sites where nerve cells connect and communicate. LTP is the synaptic mechanism that underlies memory formation.

The brain cells affected by alcohol are found in the hippocampus and other brain structures involved in advanced cognitive functions. Izumi and first author Kazuhiro Tokuda, MD, research instructor of psychiatry, studied slices of the hippocampus from the rat brain.

When they treated hippocampal cells with moderate amounts of alcohol, LTP was unaffected, but exposing the cells to large amounts of alcohol inhibited the memory formation mechanism.

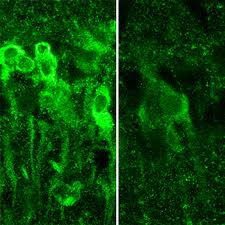

IMAGE:When exposed to large amounts of alcohol, neurons in the hippocampus produce steroids (shown in bright green, at left), which inhibit the formation of memory.

"It takes a lot of alcohol to block LTP and memory," says senior investigator Charles F. Zorumski, MD, the Samuel B. Guze Professor and head of the Department of Psychiatry. "But the mechanism isn't straightforward. The alcohol triggers these receptors to behave in seemingly contradictory ways, and that's what actually blocks the neural signals that create memories. It also may explain why individuals who get highly intoxicated don't remember what they did the night before."

But not all NMDA receptors are blocked by alcohol. Instead, their activity is cut roughly in half.

"The exposure to alcohol blocks some NMDA receptors and activates others, which then trigger the neuron to manufacture these steroids," Zorumski says.

The scientists point out that alcohol isn't causing blackouts by killing neurons. Instead, the steroids interfere with synaptic plasticity to impair LTP and memory formation.

"Alcohol isn't damaging the cells in any way that we can detect," Zorumski says. "As a matter of fact, even at the high levels we used here, we don't see any changes in how the brain cells communicate. You still process information. You're not anesthetized. You haven't passed out. But you're not forming new memories."

Stress on the hippocampal cells also can block memory formation. So can consumption of other drugs. When combined, alcohol and certain other drugs are much more likely to cause blackouts than either substance alone.

The researchers found that if they could block the manufacture of steroids by neurons, they also could preserve LTP in the rat hippocampus. And they did that with drugs called 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. These include finasteride and dutasteride, which are commonly prescribed to reduce a man's enlarged prostate gland. In the brain, however, those substances seem to preserve memory.

"We would expect there may be some differences in the effects of alcohol on patients taking these drugs," Izumi says. "Perhaps men taking the drugs would be less likely to experience intoxication blackouts."

The researchers plan to study 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors to see how easily they get into the brain and to determine whether those drugs, or similar substances, might someday play a role in preserving memory.

Tokuda K, Izumi Y, Zorumski CF. Ethanol enhances neurosteroidogenesis in hippocampal pyramidal neurons by paradoxical NMDA receptor activation, The Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 31(27), pp. 9905-9909. July 6, 2011.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by the Bantley Foundation.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Labels:

induced,

memory,

neurons,

Social Worker Continuing Education

April 24, 2012

Stress about wife's breast cancer can harm a man's health

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Caring for a wife with breast cancer can have a measurable negative effect on men's health, even years after the cancer diagnosis and completion of treatment, according to recent research.

Men who reported the highest levels of stress in relation to their wives' cancer were at the highest risk for physical symptoms and weaker immune responses, the study showed.

The researchers sought to determine the health effects of a recurrence of breast cancer on patients' male caregivers, but found that how stressed the men were about the cancer had a bigger influence on their health than did the current status of their wives' disease.

The findings imply that clinicians caring for breast cancer patients could help their patients by considering the caregivers' health as well, the researchers say.

This care could include screening caregivers for stress symptoms and encouraging them to participate in stress management, relaxation or other self-care activities, said Sharla Wells-Di Gregorio, lead author of the study and assistant professor of psychiatry and psychology at Ohio State University.

"If you care for the caregiver, your patient gets better care, too," said Kristen Carpenter, a postdoctoral researcher in psychology at Ohio State and a study co-author LSW Continuing Education

The research is published in a recent issue of the journal Brain, Behavior and Immunity.

Thirty-two men participated in the study, including 16 whose wives had experienced a breast cancer recurrence an average of eight months before the study began and approximately five years after the initial cancer diagnosis. These men were matched with 16 men whose wives' cancers were similar, but who remained disease-free about six years after the initial diagnosis.

The participants completed several questionnaires measuring levels of psychological stress related to their wives' cancers, physical symptoms related to stress, and the degree to which fatigue interfered with their daily functioning. Researchers tested their immune function by analyzing white-blood-cell activation in response to three different types of antigens, or substances that prompt the body to produce an immune response.

The men's median age was 58 years and they had been married, on average, for 26 years. Almost all of the participants were white.

In general, the men whose wives had experienced a recurrence of cancer reported higher levels of stress, greater interference from fatigue and more physical symptoms, such as headaches and abdominal pain, than did men whose wives had remained disease-free.

The subjective stress assessment used in the study, called the Impact of Events Scale, measures intrusive experiences and thoughts, as well as attempts to avoid people and places that serve as painful reminders. The scale produces a score between 0 and 75; in this case, the higher the score, the more stressed the men were in relation to their wives' cancer.

Overall, the men in the study produced an average score of 17.59. Men whose wives' cancer had recurred scored 26.25 as a group, and men whose wives were disease-free scored 8.94. According to the scale, scores above nine suggest a likely effect from the events, and scores between 26 and 43 indicate an event has had a powerful effect on a person's stress level. Scores over 33 suggest clinically significant distress.

"The scores reported here are quite high, substantially higher than we see in our cancer patient samples outside the first year," Carpenter said. "Guilt, depression, fear of loss – all of those things are stressful. And this is not an acute stressor that lasts a few weeks. It's a chronic stress that lasts for years."

The participants also reported, on average, a total of approximately seven stress-related physical symptoms. Men with wives with recurrent cancer reported nine symptoms, on average, and those whose wives were disease-free reported fewer than five symptoms, on average. These symptoms varied, but included headaches, gastrointestinal problems, coughing and nausea.

When the analysis took into consideration the impact of men's perceived stress in relation to their wives' cancer, higher stress was associated with compromised immune function: Specifically, men with the highest scores on the stress scale also showed the lowest immune responses to two of the three antigens. Previous research has suggested that people with an impaired immune response are more susceptible to infection and might not respond well to vaccines.

"Caregivers are called hidden patients because when they go in for appointments with their spouses, very few people ask how the caregiver is doing," said Wells-Di Gregorio, who works in Ohio State's Center for Palliative Care. "These men are experiencing significant distress and physical complaints, but often do not seek medical care for themselves due to their focus on their wives' illness."

In these men undergoing chronic stress, the researchers said that it remains unclear whether the immune dysregulation causes more physical symptoms, or stress causes the symptoms and the impaired immune response.

Wells-Di Gregorio noted that the stress effect might have been even more pronounced than what they observed because disease-free spouses were more reluctant to participate in the study.

"We found that many were not willing to participate because they said they didn't want to think about cancer again," she said.

This research was supported by the Ann and Herbert Siegel American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship, the Longaberger Company-American Cancer Society Grant for Breast Cancer Research, the U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity Grants, the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Co-authors included Caroline Dorfman and Hae-Chung Yang of Ohio State's Department of Psychology; Laura Simonelli of the Christiana Care Health System; and William Carson III of Ohio State's Department of Surgery and Comprehensive Cancer Center

Labels:

cancer,

health,

lsw continuing education,

stress

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)