Online Newsletter Committed to Excellence in the Fields of Mental Health, Addiction, Counseling, Social Work, and Nursing

April 30, 2012

LA BioMed researchers remain at the forefront of mental health initiatives

The month of May recognized as Mental Health Awareness Month

LOS ANGELES (April 30, 2012) – With the month of May recognized nationally as Mental Health Awareness Month, the physician-researchers at the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (LA BioMed) continue to be at the forefront of mental health initiatives, engaging in clinical trials to help find therapies and treatments for individuals who suffer from mood and anxiety disorders. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), mental health concerns affect 1 in 10 Americans today, but fewer than 25 percent of people with a diagnosable mental disorder seek treatment.

Ira Lesser, M.D., is a principal investigator at LA BioMed and Chair, Department of Psychiatry, at Harbor-UCLA. At LA BioMed, he has led a number of clinical trials on mood and anxiety disorders, including the largest ever conducted on depression – Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) – a study funded by the NIMH. LA BioMed was one of 41 clinical sites participating, enrolling the greatest number of individuals and was the highest primary care enrolling site in the country.

"With a growing number of individuals being diagnosed with a mental health disorder, it's imperative that we educate these individuals as to the options available to them, and also encourage them to seek treatment," said Dr. Lesser. "At LA BioMed, we are working to develop treatments and therapies that will not only help to cure but also help individuals cope with their existing conditions in the long term."

In addition to STAR*D, Dr. Lesser and his staff (Karl Burgoyne, M.D., Benjamin Furst, M.D., Deborah Flores, M.D.) are working on other clinical trials including Biomarkers for Rapid Identification of Treatment Effectiveness in Major Depression (BRITE) and Biomarkers for Outcomes in Late-Life Depression (BOLD).

Working alongside Dr. Lesser is LA BioMed investigator Michele Berk, Ph.D., who is directing a multi-site, randomized clinical trial that tests the effects of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) on teenagers who have attempted suicide or engaged in self-harm behaviors, such as cutting. Suicide now ranks as the third leading cause of death in the U.S. among youth ages 10-19. DBT has been shown to be effective in reducing suicidal behavior in adults with depression and personality disorders. Sponsored by the NIMH, this study is the first such clinical trial in the U.S. to test the effectiveness of DBT in adolescents.

John W. Tsuang, M.D., in conjunction with Steven J. Shoptaw, Ph.D., from the UCLA Department of Family Medicine, is spearheading a Phase I clinical safety trial that for the first time examines the effects of Ibudilast when administered with metamphetamine (MA), an addictive stimulant that is closely related to amphetamine. Funded by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), this study will help to determine the effects of Ibudilast - combined with relevant doses of MA - on heart rate and blood pressure, and whether or not Ibudilast alters the way in which the body absorbs, distributes, and metabolizes MA. The development of one or more medications to reduce MA abuse, when implemented with evidence-based behavioral and counseling interventions, would have obvious public health significance. Dr. Tsuang is hoping that following the initial safety trial, physicians will be able to utilize Ibudilast in treating patients with MA dependence to help them improve memory and reduce the damage done to their central nervous system due to MA abuse social worker continuing education

About LA BioMed

Founded in 1952, LA BioMed is one of the country's leading nonprofit independent biomedical research institutes. It has approximately 100 principal researchers conducting studies into improved treatments and cures for cancer, inherited diseases, infectious diseases, illnesses caused by environmental factors and more. It also educates young scientists and provides community services, including prenatal counseling and childhood nutrition programs. LA BioMed is academically affiliated with the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and located on the campus of Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. For more information, please visit www.LABioMed.org

April 29, 2012

Dual medications for depression increases costs, side effects with no benefit to patients

Taking two medications for depression does not hasten recovery from the condition that affects 19 million Americans each year, researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have found in a national study.

"Clinicians should not rush to prescribe combinations of antidepressant medications as first-line treatment for patients with major depressive disorder," said Dr. Madhukar H. Trivedi, professor of psychiatry and chief of the division of mood disorders at UT Southwestern and principal investigator of the study, which is available online today and is scheduled for publication in an upcoming issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry.

"The clinical implications are very clear – the extra cost and burden of two medications is not worthwhile as a first treatment step," he said.

In the Combining Medication to Enhance Depression Outcomes, or CO-MED, study, researchers at 15 sites across the country studied 665 patients ages 18 to 75 with major depressive disorder. Three treatment groups were formed and prescribed antidepressant medications already approved by the Food and Drug Administration. One group received escitalopram (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, or SSRI) and a placebo; the second group received the same SSRI paired with bupropion (a non-tricyclic antidepressant); and a third group took different antidepressants: venlafaxine (a tetracyclic antidepressant) and mirtazapine (a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor). The study was conducted from March 2008 through February 2009 LSW Continuing Education

After 12 weeks of treatment, remission and response rates were similar across the three groups: 39 percent, 39 percent and 38 percent, respectively, for remission, and about 52 percent in all three groups for response. After seven months of treatment, remission and response rates across the three groups remained similar, but side effects were more frequent in the third group.

Only about 33 percent of depressed patients go into remission in the first 12 weeks of treatment with antidepressant medication, as Dr. Trivedi and colleagues previously reported from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression, or STAR*D, study. STAR*D was the largest study ever undertaken on the treatment of major depressive disorder and is considered a benchmark in the field of depression research. That six-year, $33 million study initially included more than 4,000 patients from sites across the country. Dr. Trivedi was a co-principal investigator of STAR*D.

The next step, Dr. Trivedi said, is to study biological markers of depression to see if researchers can predict response to antidepressant medication and, thus, improve overall outcomes.

###

Other UT Southwestern researchers involved in the study were Drs. Benji Kurian and David Morris, assistant professors of psychiatry; Dr. Diane Warden, associate professor of psychiatry; and Dr. Mustafa Husain, professor of psychiatry, internal medicine, and neurology and neurotherapeutics. Former UT Southwestern professor Dr. A. John Rush, now with the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore, and researchers from the University of Pittsburgh; Massachusetts General Hospital; Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; the University of California, Los Angeles; Vanderbilt University; Harbor-UCLA Medical Center; Virginia Commonwealth University; and Columbia University Medical Center also contributed.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Organon and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals provided the medications.

Visit http://www.utsouthwestern.org/neurosciences to learn more about UT Southwestern's clinical services in neurosciences, including psychiatry.

This news release is available on our World Wide Web home page at www.utsouthwestern.edu/home/news/index.html

To automatically receive news releases from UT Southwestern via email, subscribe at www.utsouthwestern.edu/receivenews

April 27, 2012

Most Children with Rapidly Shifting Moods Don’t Have Bipolar Disorder

Relatively few children with rapidly shifting moods and high energy have bipolar disorder, though such symptoms are commonly associated with the disorder. Instead, most of these children have other types of mental disorders, according to an NIMH-funded study published online ahead of print in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry on October 5, 2010.

Background

Some parents who take their child to a mental health clinic for assessment report that the child has rapid swings between emotions (usually anger, elation, and sadness) coupled with extremely high energy levels. Some researchers suggest that this is how mania—an important component of bipolar disorder—appears in children. How mania and bipolar disorder are defined in children is important because rapid mood swings and high energy are common among youth.

Furthermore, many experts believe that overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder in youth may play a role in the increasing numbers of children being diagnosed with and treated for bipolar disorder. In choosing proper treatment, it is important to know whether children with rapid mood swings and high energy have an early or mild form of bipolar disorder, or instead have a different mental disorder CADC I & II Continuing Education

In the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) study, Robert Findling, M.D., of Case Western Reserve University, and colleagues assessed 707 children, ages 6-12, who were referred for mental health treatment. Of the participants, 621 were rated as having rapid swings between emotions and high energy levels, described as "elevated symptoms of mania" (ESM-positive). Parents of the other 86 children did not report rapid mood swings. These participants were deemed ESM-negative.

Results of the Study

At baseline, all but 14 participants had at least one mental disorder, and many had two or more. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was the most frequent diagnosis, affecting roughly 76 percent in both the ESM-positive and ESM-negative groups. However, only 39 percent were receiving treatment with a stimulant, the most common medication treatment for ADHD, at the start of the study.

Only 11 percent of those with rapid mood swings and high energy (69 out of 621) and 6 percent of those without these symptoms (5 out of 86) had bipolar disorder, meaning that only this small percentage had ever experienced a manic episode, as defined by the current diagnostic system. Of the children with rapid mood swings and high energy, another 12 percent (75 children) had a form of bipolar disorder that includes much shorter manic episodes.

Compared to children without rapid mood swings and high energy, those with these symptoms:

Reported more symptoms of depression, anxiety, manic symptoms, and symptoms of ADHD

Had lower functioning at home, school, or with peers

Were more likely to have a disruptive behavior disorder (oppositional defiant disorder and/or conduct disorder).

Significance

Given that 75 percent of ESM-positive youth did not meet the diagnostic criteria for any bipolar disorder, the researchers suggest that bipolar disorder may not be common among children who experience rapid swings between emotions and high energy levels. Nevertheless, children with these symptoms experience significant impairments due to mood and behavior problems.

The researchers also noted that ESM-positive and ESM-negative youth were prescribed psychotropic medications—including antipsychotics—at similar rates. Further study may provide insight into how serious mental illnesses should be treated in children.

What's Next

The study participants will be re-assessed every 6 months for up to 5 years, allowing the LAMS researchers to determine which children with rapid mood swings and high energy develop bipolar disorder later in life. Such research may inform efforts to identify early markers or predictors of the illness as well as possible protective factors.

Reference

Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, Fristad MA, Birmaher B, Kowatch RA, Arnold E, Frazier TW, Axelson D, Ryan N, Demeter CA, Gill MK, Fields B, Depew J, Kennedy SM, Marsh L, Rowles BM, Horwitz SM. Characteristics of Children With Elevated Symptoms of Mania: The Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) Study. J Clin Psychiatr. Epub 2010 Oct 5.

April 26, 2012

Agent Reduces Autism-like Behaviors in Mice

Press Release • April 25, 2012

Agent Reduces Autism-like Behaviors in Mice

Boosts Sociability, Quells Repetitiveness – NIH Study

National Institutes of Health researchers have reversed behaviors in mice resembling two of the three core symptoms of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). An experimental compound, called GRN-529, increased social interactions and lessened repetitive self-grooming behavior in a strain of mice that normally display such autism-like behaviors, the researchers say.

GRN-529 is a member of a class of agents that inhibit activity of a subtype of receptor protein on brain cells for the chemical messenger glutamate, which are being tested in patients with an autism-related syndrome. Although mouse brain findings often don’t translate to humans, the fact that these compounds are already in clinical trials for an overlapping condition strengthens the case for relevance, according to the researchers.

“Our findings suggest a strategy for developing a single treatment that could target multiple diagnostic symptoms,” explained Jacqueline Crawley, Ph.D., of the NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). “Many cases of autism are caused by mutations in genes that control an ongoing process – the formation and maturation of synapses, the connections between neurons. If defects in these connections are not hard-wired, the core symptoms of autism may be treatable with medications.”

Crawley, Jill Silverman, Ph.D., and colleagues at NIMH and Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development, Groton, CT, report on their discovery April 25th, 2012 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"These new results in mice support NIMH-funded research in humans to create treatments for the core symptoms of autism,” said NIMH director Thomas R. Insel, M.D. “While autism has been often considered only as a disability in need of rehabilitation, we can now address autism as a disorder responding to biomedical treatments." social worker ceus

Crawley’s team followed-up on clues from earlier findings hinting that inhibitors of the receptor, called mGluR5, might reduce ASD symptoms. This class of agents – compounds similar to GRN-529, used in the mouse study – are in clinical trials for patients with the most common form of inherited intellectual and developmental disabilities, Fragile X syndrome, about one third of whom also meet criteria for ASDs.

To test their hunch, the researchers examined effects of GRN-529 in a naturally occurring inbred strain of mice that normally display autism-relevant behaviors. Like children with ASDs, these BTBR mice interact and communicate relatively less with each other and engage in repetitive behaviors – most typically, spending an inordinate amount of time grooming themselves.

Crawley’s team found that BTBR mice injected with GRN-529 showed reduced levels of repetitive self-grooming and spent more time around – and sniffing nose-to-nose with – a strange mouse.

Moreover, GRN-529 almost completely stopped repetitive jumping in another strain of mice.

“These inbred strains of mice are similar, behaviorally, to individuals with autism for whom the responsible genetic factors are unknown, which accounts for about three fourths of people with the disorders,” noted Crawley. “Given the high costs – monetary and emotional – to families, schools, and health care systems, we are hopeful that this line of studies may help meet the need for medications that treat core symptoms.”

Reference:

Silverman JL, Smith DG, Rizzo SJS, Karras MN, Turner SM, Tolu SS, Bryce DK, Smith DL, Fonseca K, Ring RH, Crawley, JN. Negative allosteric modulation of the MGluR5 receptor reduces repetitive behaviors and rescues social deficits in mouse models of autism. April 25, 2012, Science Translational Medicine.

Labels:

autism,

genes,

Social Worker CEUs,

study

April 25, 2012

In a nationally representative survey of 12- to 17-year-old youth and their trauma experiences, 39 percent reported witnessing violence, 17 percent reported physical assault, and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault.

April 2012 Social Media Message

In a nationally representative survey of 12- to 17-year-old youth and their trauma experiences, 39 percent reported witnessing violence, 17 percent reported physical assault, and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault.

With help from families, friends, providers, and other Heroes of Hope, children and youth can be resilient when dealing with trauma. Visit www.samhsa.gov/children to learn more.

When looking at rates of exposure to traumatic events, a nationally representative survey reported that among 12- to 17-year-old youth, 39 percent reported witnessing violence, 17 percent reported physical assault, and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault.1, 2 ceus for social workers

Research has shown that caregivers can buffer the impact of trauma and promote better outcomes for children, even under stressful times, when the following Strengthening Families Protective Factors are present:

•Parental resilience

•Social connections

•Knowledge of parenting and child development

•Concrete support in times of need

•Social and emotional competence of children3

Use these sample messages to share this childhood trauma and resilience data point with your connections on Twitter and Facebook and via email.

Twitter: 39% of 12- to 17-year-old youths have reported witnessing violence, learn more: http://1.usa.gov/Ie4UjT via @samhsagov #HeroesofHope

Facebook: A national survey of 12- to 17-year-old youths found that 17 percent reported physical assault and 8 percent reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual assault. Learn more about the behavioral health impact of traumatic events on children and youth and pass it on to observe National Children's Mental Health Awareness Day: http://1.usa.gov/Ie4UjT

References:

1. Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R. (2003). Mental health needs of crime victims: Epidemiology and outcomes. Journal of Traumatic Stress.16(2),119–132. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1023/A:1022891005388/abstract .

2.Saunders BE. (2003). Understanding Children Exposed to Violence Toward an Integration of Overlapping Fields. National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center. J Interpers Violence. 18(4) 356-376. Retrieved from http://jiv.sagepub.com/content/18/4/356.short .

3.Horton, C. (2003). Protective factors literature review. Early care and education programs and the prevention of child abuse and neglect. Center for the Study of Social Policy.

Labels:

assault,

ceus for social workers,

child development,

emotional,

violence

The biology behind alcohol-induced blackouts

A person who drinks too much alcohol may be able to perform complicated tasks, such as dancing, carrying on a conversation or even driving a car, but later have no memory of those escapades. These periods of amnesia, commonly known as "blackouts," can last from a few minutes to several hours.

Now, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, neuroscientists have identified the brain cells involved in blackouts and the molecular mechanism that appears to underlie them. They report July 6, 2011, in The Journal of Neuroscience, that exposure to large amounts of alcohol does not necessarily kill brain cells as once was thought. Rather, alcohol interferes with key receptors in the brain, which in turn manufacture steroids that inhibit long-term potentiation (LTP), a process that strengthens the connections between neurons and is crucial to learning and memory.

Better understanding of what occurs when memory formation is inhibited by alcohol exposure could lead to strategies to improve memory.

"The mechanism involves NMDA receptors that transmit glutamate, which carries signals between neurons," says Yukitoshi Izumi, MD, PhD, research professor of psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. "An NMDA receptor is like a double-edged sword because too much activity and too little can be toxic. We've found that exposure to alcohol inhibits some receptors and later activates others, causing neurons to manufacture steroids that inhibit LTP and memory formation." social worker continuing education

Izumi says the various receptors involved in the cascade interfere with synaptic plasticity in the brain's hippocampus, which is known to be important in cognitive function. Just as plastic bends and can be molded into different shapes, synaptic plasticity is a term scientists use to describe the changeable properties of synapses, the sites where nerve cells connect and communicate. LTP is the synaptic mechanism that underlies memory formation.

The brain cells affected by alcohol are found in the hippocampus and other brain structures involved in advanced cognitive functions. Izumi and first author Kazuhiro Tokuda, MD, research instructor of psychiatry, studied slices of the hippocampus from the rat brain.

When they treated hippocampal cells with moderate amounts of alcohol, LTP was unaffected, but exposing the cells to large amounts of alcohol inhibited the memory formation mechanism.

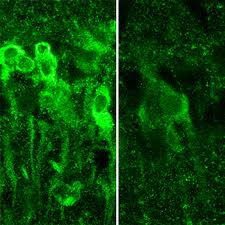

IMAGE:When exposed to large amounts of alcohol, neurons in the hippocampus produce steroids (shown in bright green, at left), which inhibit the formation of memory.

"It takes a lot of alcohol to block LTP and memory," says senior investigator Charles F. Zorumski, MD, the Samuel B. Guze Professor and head of the Department of Psychiatry. "But the mechanism isn't straightforward. The alcohol triggers these receptors to behave in seemingly contradictory ways, and that's what actually blocks the neural signals that create memories. It also may explain why individuals who get highly intoxicated don't remember what they did the night before."

But not all NMDA receptors are blocked by alcohol. Instead, their activity is cut roughly in half.

"The exposure to alcohol blocks some NMDA receptors and activates others, which then trigger the neuron to manufacture these steroids," Zorumski says.

The scientists point out that alcohol isn't causing blackouts by killing neurons. Instead, the steroids interfere with synaptic plasticity to impair LTP and memory formation.

"Alcohol isn't damaging the cells in any way that we can detect," Zorumski says. "As a matter of fact, even at the high levels we used here, we don't see any changes in how the brain cells communicate. You still process information. You're not anesthetized. You haven't passed out. But you're not forming new memories."

Stress on the hippocampal cells also can block memory formation. So can consumption of other drugs. When combined, alcohol and certain other drugs are much more likely to cause blackouts than either substance alone.

The researchers found that if they could block the manufacture of steroids by neurons, they also could preserve LTP in the rat hippocampus. And they did that with drugs called 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. These include finasteride and dutasteride, which are commonly prescribed to reduce a man's enlarged prostate gland. In the brain, however, those substances seem to preserve memory.

"We would expect there may be some differences in the effects of alcohol on patients taking these drugs," Izumi says. "Perhaps men taking the drugs would be less likely to experience intoxication blackouts."

The researchers plan to study 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors to see how easily they get into the brain and to determine whether those drugs, or similar substances, might someday play a role in preserving memory.

Tokuda K, Izumi Y, Zorumski CF. Ethanol enhances neurosteroidogenesis in hippocampal pyramidal neurons by paradoxical NMDA receptor activation, The Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 31(27), pp. 9905-9909. July 6, 2011.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by the Bantley Foundation.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Labels:

induced,

memory,

neurons,

Social Worker Continuing Education

April 24, 2012

Stress about wife's breast cancer can harm a man's health

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Caring for a wife with breast cancer can have a measurable negative effect on men's health, even years after the cancer diagnosis and completion of treatment, according to recent research.

Men who reported the highest levels of stress in relation to their wives' cancer were at the highest risk for physical symptoms and weaker immune responses, the study showed.

The researchers sought to determine the health effects of a recurrence of breast cancer on patients' male caregivers, but found that how stressed the men were about the cancer had a bigger influence on their health than did the current status of their wives' disease.

The findings imply that clinicians caring for breast cancer patients could help their patients by considering the caregivers' health as well, the researchers say.

This care could include screening caregivers for stress symptoms and encouraging them to participate in stress management, relaxation or other self-care activities, said Sharla Wells-Di Gregorio, lead author of the study and assistant professor of psychiatry and psychology at Ohio State University.

"If you care for the caregiver, your patient gets better care, too," said Kristen Carpenter, a postdoctoral researcher in psychology at Ohio State and a study co-author LSW Continuing Education

The research is published in a recent issue of the journal Brain, Behavior and Immunity.

Thirty-two men participated in the study, including 16 whose wives had experienced a breast cancer recurrence an average of eight months before the study began and approximately five years after the initial cancer diagnosis. These men were matched with 16 men whose wives' cancers were similar, but who remained disease-free about six years after the initial diagnosis.

The participants completed several questionnaires measuring levels of psychological stress related to their wives' cancers, physical symptoms related to stress, and the degree to which fatigue interfered with their daily functioning. Researchers tested their immune function by analyzing white-blood-cell activation in response to three different types of antigens, or substances that prompt the body to produce an immune response.

The men's median age was 58 years and they had been married, on average, for 26 years. Almost all of the participants were white.

In general, the men whose wives had experienced a recurrence of cancer reported higher levels of stress, greater interference from fatigue and more physical symptoms, such as headaches and abdominal pain, than did men whose wives had remained disease-free.

The subjective stress assessment used in the study, called the Impact of Events Scale, measures intrusive experiences and thoughts, as well as attempts to avoid people and places that serve as painful reminders. The scale produces a score between 0 and 75; in this case, the higher the score, the more stressed the men were in relation to their wives' cancer.

Overall, the men in the study produced an average score of 17.59. Men whose wives' cancer had recurred scored 26.25 as a group, and men whose wives were disease-free scored 8.94. According to the scale, scores above nine suggest a likely effect from the events, and scores between 26 and 43 indicate an event has had a powerful effect on a person's stress level. Scores over 33 suggest clinically significant distress.

"The scores reported here are quite high, substantially higher than we see in our cancer patient samples outside the first year," Carpenter said. "Guilt, depression, fear of loss – all of those things are stressful. And this is not an acute stressor that lasts a few weeks. It's a chronic stress that lasts for years."

The participants also reported, on average, a total of approximately seven stress-related physical symptoms. Men with wives with recurrent cancer reported nine symptoms, on average, and those whose wives were disease-free reported fewer than five symptoms, on average. These symptoms varied, but included headaches, gastrointestinal problems, coughing and nausea.

When the analysis took into consideration the impact of men's perceived stress in relation to their wives' cancer, higher stress was associated with compromised immune function: Specifically, men with the highest scores on the stress scale also showed the lowest immune responses to two of the three antigens. Previous research has suggested that people with an impaired immune response are more susceptible to infection and might not respond well to vaccines.

"Caregivers are called hidden patients because when they go in for appointments with their spouses, very few people ask how the caregiver is doing," said Wells-Di Gregorio, who works in Ohio State's Center for Palliative Care. "These men are experiencing significant distress and physical complaints, but often do not seek medical care for themselves due to their focus on their wives' illness."

In these men undergoing chronic stress, the researchers said that it remains unclear whether the immune dysregulation causes more physical symptoms, or stress causes the symptoms and the impaired immune response.

Wells-Di Gregorio noted that the stress effect might have been even more pronounced than what they observed because disease-free spouses were more reluctant to participate in the study.

"We found that many were not willing to participate because they said they didn't want to think about cancer again," she said.

This research was supported by the Ann and Herbert Siegel American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship, the Longaberger Company-American Cancer Society Grant for Breast Cancer Research, the U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity Grants, the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Co-authors included Caroline Dorfman and Hae-Chung Yang of Ohio State's Department of Psychology; Laura Simonelli of the Christiana Care Health System; and William Carson III of Ohio State's Department of Surgery and Comprehensive Cancer Center

Labels:

cancer,

health,

lsw continuing education,

stress

April 23, 2012

Gatekeeper of brain steroid signals boosts emotional resilience to stress

PHILADELPHIA - A cellular protein called HDAC6, newly characterized as a gatekeeper of steroid biology in the brain, may provide a novel target for treating and preventing stress-linked disorders, such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), according to research from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Glucocorticoids are natural steroids secreted by the body during stress. A small amount of these hormones helps with normal brain function, but their excess is a precipitating factor for stress-related disorders.

Glucocorticoids exert their effects on mood by acting on receptors in the nucleus of emotion–regulating neurons, such as those producing the neurotransmitter serotonin. For years, researchers have searched for ways to prevent deleterious effects of stress by blocking glucocorticoids in neurons. However, this has proved difficult to do without simultaneously interfering with other functions of these hormones, such as the regulation of immune function and energy metabolism.

In a recent Journal of Neuroscience paper, the lab of Olivier Berton, PhD, assistant professor of Psychiatry, shows how a regulator of glucocorticoid receptors may provide a path towards resilience to stress by modulating glucocorticoid signaling in the brain. The protein HDAC6, which is particularly enriched in serotonin pathways, as well as in other mood-regulatory regions in both mice and humans, is ideally distributed in the brain to mediate the effect of glucocorticoids on mood and emotions. HDAC6 likely does this by controlling the interactions between glucocorticoid receptors and hormones in these serotonin circuits ceus for social workers

Experiments that first alerted Berton and colleagues to a peculiar role of HDAC6 in stress adaptation came from an approach that reproduces certain clinical features of traumatic stress and depression in mice. The animals are exposed to brief bouts of aggression from trained "bully" mice. In most aggression-exposed mice this experience leads to the development of a lasting form of social aversion that can be treated by chronic administration of antidepressants.

In contrast, a portion of mice exposed to chronic aggression consistently express spontaneous resilience to the stress and do not develop any symptoms. By comparing gene expression in the brains of spontaneously resilient and vulnerable mice, Berton and colleagues discovered that reducing HDAC6 expression is a hallmark of naturally resilient animals. While aggression also caused severe changes in the shape of serotonin neurons and their capacity to transmit electrical signals in vulnerable mice, stress-resilient mice, in contrast, escaped most of these neurobiological changes.

To better understand the link between HDAC6 and the development of stress resilience, Berton and colleagues devised a genetic approach to directly manipulate HDAC6 levels in neurons: Deletion of HDAC6 in serotonin neurons -- the densest HDAC6-expressing cell group in the mouse brain -- dramatically reduced social and anxiety symptoms in mice exposed to bullies and also fully prevented neurobiological changes due to stress, fully mimicking a resilient phenotype.

Using biochemical assays, Berton's team showed it is by promoting reversible chemical changes onto a heat shock chaperone protein, Hsp90, that HDAC6 deletion is able to literally switch off the effects of glucocorticoid hormones on social and anxiety behaviors.

Chaperones are proteins that help with the folding or unfolding and the assembly or disassembly of protein complexes. The way in which glucocorticoid receptor chaperoning and stress are linked is not well understood. Yet, genetic variations in certain components of the glucocorticoid receptor chaperone complex have been associated with the development of stress-related disorders and individual variability in therapeutic responses to antidepressants.

"We provide pharmacological and genetic evidence indicating that HDAC6 controls certain aspects of Hsp90 structure and function in the brain, and thereby modulates protein interactions, as well as hormone- and stress-induced glucocorticoid receptor signaling and behavior," explains Berton.

Together, these results identify HDAC6 as a possible stress vulnerability biomarker and point to pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 as a potential new strategy for antidepressant interventions through regulation of Hsp90 in glucocorticoid signaling in serotonin neurons.

Co-first-authors are Julie Espallergues and Sarah L. Teegarden, along with Avin Veerakumar, Janette Boulden, Collin Challis, Jeanine Jochems, Michael Chan, Tess Petersen, Chang-Gyu Hahn, Irwin Lucki, and Sheryl G. Beck, all from Penn. Other authors are Evan Deneris, from Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, and Patrick Matthias, Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, Basel, Switzerland.

This work was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health grants MH087581 and MH0754047 and grants from the International Mental Health Research Organization and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine is currently ranked #2 in U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $479.3 million awarded in the 2011 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top 10 hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; and Pennsylvania Hospital - the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Penn Medicine also includes additional patient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2011, Penn Medicine provided $854 million to benefit our community.

Labels:

brain,

ceus for social workers,

emotion,

stress

April 22, 2012

Phobia's effect on perception of feared object allows fear to persist

COLUMBUS, Ohio – The more afraid a person is of a spider, the bigger that individual perceives the spider to be, new research suggests.

In the context of a fear of spiders, this warped perception doesn't necessarily interfere with daily living. But for individuals who are afraid of needles, for example, the conviction that needles are larger than they really are could lead people who fear injections to avoid getting the health care they need.

A better understanding of how a phobia affects the perception of feared objects can help clinicians design more effective treatments for people who seek to overcome their fears, according to the researchers.

In this study, participants who feared spiders were asked to undergo five encounters with live spiders – tarantulas, in fact – and then provide size estimates of the spiders after those encounters ended. The more afraid the participants said they were of the spiders, the larger they estimated the spiders had been.

"If one is afraid of spiders, and by virtue of being afraid of spiders one tends to perceive spiders as bigger than they really are, that may feed the fear, foster that fear, and make it difficult to overcome," said Michael Vasey, professor of psychology at Ohio State University and lead author of the study.

"When it comes to phobias, it's all about avoidance as a primary means of keeping oneself safe. As long as you avoid, you can't discover that you're wrong. And you're stuck. So to the extent that perceiving spiders as bigger than they really are fosters fear and avoidance, it then potentially is part of this cycle that feeds the phobia that leads to its persistence continuing education for social workers

"We're trying to understand why phobias persist so we can better target treatments to change those reasons they persist."

The study is published in a recent issue of the Journal of Anxiety Disorders.

The researchers recruited 57 people who self-identified as having a spider phobia. Each participant then interacted at specific time points over a period of eight weeks with five different varieties of tarantulas varying in size from about 1 to 6 inches long.

The spiders were contained in an uncovered glass tank. Participants began their encounters 12 feet from the tank and were asked to approach the spider. Once they were standing next to the tank, they were asked to guide the spider around the tank by touching it with an 8-inch probe, and later with a shorter probe.

Throughout these encounters, researchers asked participants to report how afraid they were feeling on a scale of 0-100 according to an index of subjective units of distress. After the encounters, participants completed additional self-report measures of their specific fear of spiders, any panic symptoms they experienced during the encounters with the spiders, and thoughts about fear reduction and future spider encounters.

Finally, the research participants estimated the size of the spiders – while no longer being able to see them – by drawing a single line on an index card indicating the length of the spider from the tips of its front legs to the tips of its back legs.

An analysis of the results showed that higher average peak ratings of distress during the spider encounters were associated with estimates that the spiders were larger than they really were. Similar positive associations were seen between over-estimates of spider size and participants' higher average peak levels of anxiety, higher average numbers of panic symptoms and overall spider fear. These findings have been supported in later studies with broader samples of people with varying levels of fear of spiders.

"It would appear from that result that fear is driving or altering the perception of the feared object, in this case a spider," said Vasey, also the director of research for the psychology department's Anxiety and Stress Disorders Clinic. "We already knew fear and anxiety alter thoughts about the feared thing. For example, the feared outcome is interpreted as being more likely than it really is. But this study shows that even perception is altered by fear. In this case, the feared spider is seen as being bigger. And that may serve as a maintaining factor for the fear."

The approach tasks with the spiders are a classic example of exposure therapy, a common treatment for people with phobias. Though this therapy is known to be effective, scientists still do not fully understand why it works. And for some, the effects don't last – but it is difficult to predict who will have a relapse of fear, Vasey said.

He and colleagues are studying these biased perceptions as well as attitudes with hopes that the new knowledge will enhance treatment for people with various phobias. The work suggests that fear not only alters one's perception of the feared thing, but also can influence a person's automatic attitude toward an object. Those who have developed an automatic negative attitude toward a feared object might have a harder time overcoming their fear.

Though individuals with arachnophobia are unlikely to seek treatment, the use of spiders in this research was a convenient way to study the complex effects of fear on visual perception and how those effects might cause fear to persist, Vasey noted.

"Ultimately, we are interested in identifying predictors of relapse so we can better measure when a person is done with treatment," he said.

This work is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Co-authors include Michael Vilensky, Jacqueline Heath, Casaundra Harbaugh, Adam Buffington and Vasey's principal collaborator, Russell Fazio, all of Ohio State's Department of Psychology.

April 18, 2012

Genetic manipulation boosts growth of brain cells linked to learning, enhances antidepressants

DALLAS -- UT Southwestern Medical Center investigators have identified a genetic manipulation that increases the development of neurons in the brain during aging and enhances the effect of antidepressant drugs.

The research finds that deleting the Nf1 gene in mice results in long-lasting improvements in neurogenesis, which in turn makes those in the test group more sensitive to the effects of antidepressants.

"The significant implication of this work is that enhancing neurogenesis sensitizes mice to antidepressants – meaning they needed lower doses of the drugs to affect 'mood' – and also appears to have anti-depressive and anti-anxiety effects of its own that continue over time," said Dr. Luis Parada, director of the Kent Waldrep Center for Basic Research on Nerve Growth and Regeneration and senior author of the study published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

Just as in people, mice produce new neurons throughout adulthood, although the rate declines with age and stress, said Dr. Parada, chairman of developmental biology at UT Southwestern. Studies have shown that learning, exercise, electroconvulsive therapy and some antidepressants can increase neurogenesis. The steps in the process are well known but the cellular mechanisms behind those steps are not.

"In neurogenesis, stem cells in the brain's hippocampus give rise to neuronal precursor cells that eventually become young neurons, which continue on to become full-fledged neurons that integrate into the brain's synapses," said Dr. Parada, an elected member of the prestigious National Academy of Sciences, its Institute of Medicine, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The researchers used a sophisticated process to delete the gene that codes for the Nf1 protein only in the brains of mice, while production in other tissues continued normally. After showing that mice lacking Nf1 protein in the brain had greater neurogenesis than controls, the researchers administered behavioral tests designed to mimic situations that would spark a subdued mood or anxiety, such as observing grooming behavior in response to a small splash of sugar water.

The researchers found that the test group mice formed more neurons over time compared to controls, and that young mice lacking the Nf1 protein required much lower amounts of anti-depressants to counteract the effects of stress. Behavioral differences between the groups persisted at three months, six months and nine months. "Older mice lacking the protein responded as if they had been taking antidepressants all their lives," said Dr. Parada.

"In summary, this work suggests that activating neural precursor cells could directly improve depression- and anxiety-like behaviors, and it provides a proof-of-principle regarding the feasibility of regulating behavior via direct manipulation of adult neurogenesis," Dr. Parada said.

Dr. Parada's laboratory has published a series of studies that link the Nf1 gene – best known for mutations that cause tumors to grow around nerves – to wide-ranging effects in several major tissues. For instance, in one study researchers identified ways that the body's immune system promotes the growth of tumors, and in another study, they described how loss of the Nf1 protein in the circulatory system leads to hypertension and congenital heart disease social worker ceus

The current study's lead author is former graduate student Dr. Yun Li, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Other co-authors include Yanjiao Li, a research associate of developmental biology, Dr. Renée McKay, assistant professor of developmental biology, both of UT Southwestern, and Dr. Dieter Riethmacher of the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Parada is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

This news release is available on our World Wide Web home page at www.utsouthwestern.edu/home/news/index.html

To automatically receive news releases from UT Southwestern via email, subscribe at www.utsouthwestern.edu/receivenews

Labels:

brain,

brain cells,

gene,

Social Worker CEU,

Social Worker CEUs

April 15, 2012

Excessive worrying may have co-evolved with intelligence

What is usually seen as pathology may aid survival of the species

Worrying may have evolved along with intelligence as a beneficial trait, according to a recent study by scientists at SUNY Downstate Medical Center and other institutions. Jeremy Coplan, MD, professor of psychiatry at SUNY Downstate, and colleagues found that high intelligence and worry both correlate with brain activity measured by the depletion of the nutrient choline in the subcortical white matter of the brain. According to the researchers, this suggests that intelligence may have co-evolved with worry in humans.

"While excessive worry is generally seen as a negative trait and high intelligence as a positive one, worry may cause our species to avoid dangerous situations, regardless of how remote a possibility they may be," said Dr. Coplan. "In essence, worry may make people 'take no chances,' and such people may have higher survival rates. Thus, like intelligence, worry may confer a benefit upon the species."

In this study of anxiety and intelligence, patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were compared with healthy volunteers to assess the relationship among intelligence quotient (IQ), worry, and subcortical white matter metabolism of choline. In a control group of normal volunteers, high IQ was associated with a lower degree of worry, but in those diagnosed with GAD, high IQ was associated with a greater degree of worry. The correlation between IQ and worry was significant in both the GAD group and the healthy control group. However, in the former, the correlation was positive and in the latter, the correlation was negative. Eighteen healthy volunteers (eight males and 10 females) and 26 patients with GAD (12 males and 14 females) served as subjects.

Previous studies have indicated that excessive worry tends to exist both in people with higher intelligence and lower intelligence, and less so in people of moderate intelligence. It has been hypothesized that people with lower intelligence suffer more anxiety because they achieve less success in life.

The results of their study, "The Relationship between Intelligence and Anxiety: An Association with Subcortical White Matter Metabolism," was published in a recent edition of Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience, and can be read at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3269637/pdf/fnevo-03-00008.pdf.

The study was selected and evaluated by a member of the Faculty of 1000 (F1000), placing it in their library of the top 2% of published articles in biology and medicine.

SUNY Downstate Medical Center, founded in 1860, was the first medical school in the United States to bring teaching out of the lecture hall and to the patient's bedside. A center of innovation and excellence in research and clinical service delivery, SUNY Downstate Medical Center comprises a College of Medicine, Colleges of Nursing and Health Related Professions, a School of Graduate Studies, a School of Public Health, University Hospital of Brooklyn, and an Advanced Biotechnology Park and Biotechnology Incubator.

SUNY Downstate ranks eighth nationally in the number of alumni who are on the faculty of American medical schools. More physicians practicing in New York City have graduated from SUNY Downstate than from any other medical school social worker continuing education

Labels:

Anxiety,

Social Worker Continuing Education,

worry

April 11, 2012

Mothers and OCD children trapped in rituals have impaired relationships

News Release: Tuesday, April 10, 2012

A new study from Case Western Reserve University finds mothers tend to be more critical of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder than they are of other children in the family. And, that parental criticism is linked to poorer outcomes for the child after treatment.

Parent criticism has been associated with child anxiety in the past, however, researchers wanted to find out if this is a characteristic of the parent or something specific to the relationship between the anxious child and the parent.

“This suggests that mothers of anxious children are not overly critical parents in general. Instead they seem to be more critical of a child with OCD than they are of other children in the home,” said Amy Przeworski, assistant professor of psychology. She is the lead author of the study, “Maternal and Child Expressed Emotion as Predictors of Treatment Response in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder,” in the recent journal, Child Psychiatry & Human Development.

OCD is found in one in 200 children, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The psychological disorder overcomes individuals with repetitive thoughts that lead to anxiety, which is then acted out in exacting routines or behaviors that can range from foot tapping to eating rituals to school or bedtime preparations.

This research evolved from other studies that found parental criticism is associated with less success in therapy and a relapse of behavior.

“Parents’ criticism may be a reaction to the child’s anxiety. This research is not blaming the parent for the child’s OCD. But it does suggest that the relationship between parents and children with OCD is important and should be a focus of treatment. This means that parents can help children with OCD to get better.” Przeworski says.

“OCD sneaks up on the kids and parents,” Przeworski says.

The psychology professor, who specializes in anxiety disorders, says some parents become concerned when their children show some early warning signs for OCD:

• Rigidity in a child, with things routinely done or said in exactly the same way or order.

• Asking for reassurance many times in the day.

• Repetition of a task from tapping the foot, checking on the stove, washing hands that the child cannot stop when asked.

• Routines that have prescribed patterns or are excessive lengthy: An example is a two-hour shower or raw and chapped hands that look like the child is wearing red gloves.

• Bedtime or dinner rituals, where there is a prescribed order for eating food, placement of food on the plate, etc.

• Temper tantrums where the child goes beyond being stubborn but has anxiety associated with them.

• Children want symmetry in appearance or things around them.

Parents initially may think it is a phase, a habit or stubbornness. Over time, the behaviors become so exacting that the child and family members have to act in prescribed ways. Parents may end up criticizing the child in an effort to get them to drop obsessive-compulsive behaviors.

The researchers videotaped interviews with 62 mother-child pairs just before the child’s OCD treatment began. Children either had medication, therapy, a combination of the two, or a placebo. The children were between the ages of 7 and 17.

Because most mothers bring their children for treatment appointments, the researchers focused on the mother’s view of their children. Mothers were asked to give a five-minute description of their relationship with the child with OCD and the mother’s relationship with the sibling closest in age to the child with OCD. The researchers asked the children to describe their relationships with their mothers and fathers.

The researchers examined the presence of criticism and emotional over-involvement (over-protection or excessive self-sacrificing) in these descriptions. The tone of the OCD child and parent tended toward criticism, they said. The other sibling received more loving expressions. Parent criticism was associated with poorer child functioning after treatment.

Przeworski said treatment of OCD has good results, but many times parents misjudge these rigid routines as stubbornness or “just going through a phase” until the behavior takes over family life. Then parents realize the behavior requires therapy professional counselor continuing education

Collaborating with Przeworski were: Lori Zoellner from University of Washington; Martin E. Franklin and Edna B. Foa, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; and Abbe Garcia and Jennifer Freeman, Brown University. The study was supported with funds from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Posted by: Susan Griffith, April 10, 2012 01:19 PM | News Topics: Official Release

A new study from Case Western Reserve University finds mothers tend to be more critical of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder than they are of other children in the family. And, that parental criticism is linked to poorer outcomes for the child after treatment.

Parent criticism has been associated with child anxiety in the past, however, researchers wanted to find out if this is a characteristic of the parent or something specific to the relationship between the anxious child and the parent.

“This suggests that mothers of anxious children are not overly critical parents in general. Instead they seem to be more critical of a child with OCD than they are of other children in the home,” said Amy Przeworski, assistant professor of psychology. She is the lead author of the study, “Maternal and Child Expressed Emotion as Predictors of Treatment Response in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder,” in the recent journal, Child Psychiatry & Human Development.

OCD is found in one in 200 children, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The psychological disorder overcomes individuals with repetitive thoughts that lead to anxiety, which is then acted out in exacting routines or behaviors that can range from foot tapping to eating rituals to school or bedtime preparations.

This research evolved from other studies that found parental criticism is associated with less success in therapy and a relapse of behavior.

“Parents’ criticism may be a reaction to the child’s anxiety. This research is not blaming the parent for the child’s OCD. But it does suggest that the relationship between parents and children with OCD is important and should be a focus of treatment. This means that parents can help children with OCD to get better.” Przeworski says.

“OCD sneaks up on the kids and parents,” Przeworski says.

The psychology professor, who specializes in anxiety disorders, says some parents become concerned when their children show some early warning signs for OCD:

• Rigidity in a child, with things routinely done or said in exactly the same way or order.

• Asking for reassurance many times in the day.

• Repetition of a task from tapping the foot, checking on the stove, washing hands that the child cannot stop when asked.

• Routines that have prescribed patterns or are excessive lengthy: An example is a two-hour shower or raw and chapped hands that look like the child is wearing red gloves.

• Bedtime or dinner rituals, where there is a prescribed order for eating food, placement of food on the plate, etc.

• Temper tantrums where the child goes beyond being stubborn but has anxiety associated with them.

• Children want symmetry in appearance or things around them.

Parents initially may think it is a phase, a habit or stubbornness. Over time, the behaviors become so exacting that the child and family members have to act in prescribed ways. Parents may end up criticizing the child in an effort to get them to drop obsessive-compulsive behaviors.

The researchers videotaped interviews with 62 mother-child pairs just before the child’s OCD treatment began. Children either had medication, therapy, a combination of the two, or a placebo. The children were between the ages of 7 and 17.

Because most mothers bring their children for treatment appointments, the researchers focused on the mother’s view of their children. Mothers were asked to give a five-minute description of their relationship with the child with OCD and the mother’s relationship with the sibling closest in age to the child with OCD. The researchers asked the children to describe their relationships with their mothers and fathers.

The researchers examined the presence of criticism and emotional over-involvement (over-protection or excessive self-sacrificing) in these descriptions. The tone of the OCD child and parent tended toward criticism, they said. The other sibling received more loving expressions. Parent criticism was associated with poorer child functioning after treatment.

Przeworski said treatment of OCD has good results, but many times parents misjudge these rigid routines as stubbornness or “just going through a phase” until the behavior takes over family life. Then parents realize the behavior requires therapy professional counselor continuing education

Collaborating with Przeworski were: Lori Zoellner from University of Washington; Martin E. Franklin and Edna B. Foa, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; and Abbe Garcia and Jennifer Freeman, Brown University. The study was supported with funds from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Posted by: Susan Griffith, April 10, 2012 01:19 PM | News Topics: Official Release

April 08, 2012

Spontaneous Gene Glitches Linked to Autism Risk with Older Dads

Non-Inherited Mutations Spotlight Role of Environment – NIH-Supported Study, Consortium ceus for nurses

Researchers have turned up a new clue to the workings of a possible environmental factor in autism spectrum disorders (ASDs): fathers were four times more likely than mothers to transmit tiny, spontaneous mutations to their children with the disorders. Moreover, the number of such transmitted genetic glitches increased with paternal age. The discovery may help to explain earlier evidence linking autism risk to older fathers.

The results are among several from a trio of new studies, supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, finding that such sequence changes in parts of genes that code for proteins play a significant role in ASDs. One of the studies determined that having such glitches boosts a child’s risk of developing autism five to 20 fold.

Taken together, the three studies represent the largest effort of its kind, drawing upon samples from 549 families to maximize statistical power. They reveal sporadic mutations widely distributed across the genome, sometimes conferring risk and sometimes not. While the changes identified don’t account for most cases of illness, they are providing clues to the biology of what are likely multiple syndromes along the autism spectrum.

“These results confirm that it’s not necessarily the size of a genetic anomaly that confers risk, but its location – specifically in biochemical pathways involved in brain development and neural connections. Ultimately, it’s this kind of knowledge that will yield potential targets for new treatments,” explained Thomas, R. Insel, M.D., director of the NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), which funded one of the studies and fostered development of the Autism Sequencing Consortium, of which all three groups are members.

Multi-site research teams led by Mark Daly, Ph.D., of the Harvard/MIT Broad Institute, Cambridge, Mass., Matthew State, M.D., Ph.D., of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and Evan Eichler, Ph.D., of the University of Washington, Seattle, report on their findings online April 4, 2012 in the journal Nature.

The study by Daly and colleagues was supported by NIMH – including funding under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The State and Eichler studies were primarily supported by the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative. The studies also acknowledge the NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, and National Institute on Child Health and Human Development and other NIH components.

All three teams sequenced the protein coding parts of genes in parents and an affected child – mostly in families with only one member touched by autism. One study also included comparisons with healthy siblings. Although these protein-coding areas represent only about 1.5 percent of the genome, they harbor 85 percent of disease-causing mutations. This strategy optimized the odds for detecting the few spontaneous errors in genetic transmission that confer autism risk from the “background noise” generated by the many more benign mutations.

Like larger deletions and duplications of genetic material previously implicated in autism and schizophrenia, the tiny point mutations identified in the current studies are typically not inherited in the conventional sense – they are not part of parents’ DNA, but become part of the child’s DNA. Most people have many such glitches and suffer no ill effects from them. But evidence is building that such mutations can increase risk for autism if they occur in pathways that disrupt brain development.

State’s team found that 14 percent of people with autism studied had suspect mutations – five times the normal rate. Eichler and colleagues traced 39 percent of such mutations likely to confer risk to a biological pathway known to be important for communications in the brain.

Although Daly and colleagues found evidence for only a modest role of the chance mutations in autism, those pinpointed were biologically related to each other and to genes previously implicated in autism.

The Eichler team turned up clues to how environmental factors might influence genetics. The high turnover in a male’s sperm cells across the lifespan increases the chance for errors to occur in the genetic translation process. These can be passed-on to the offspring’s DNA, even though they are not present in the father’s DNA. This risk may worsen with aging. The researchers discovered a four-fold marked paternal bias in the origins of 51 spontaneous mutations in coding areas of genes that was positively correlated with increasing age of the father. So such spontaneous mutations could account for findings of an earlier study that found fathers of boys with autism were six times – and of girls 17 times – more likely to be in their 40’s than their 20’s.

“We now have a path forward to capture a great part of the genetic variability in autism – even to the point of being able to predict how many mutations in coding regions of a gene would be needed to account for illness,” said Thomas Lehner, Ph.D., chief of the NIMH Genomics Research Branch, which funded the Daly study and helped to create the Autism Sequencing Consortium. “These studies begin to tell a more comprehensive story about the molecular underpinnings of autism that integrates previously disparate pieces of evidence.”

References

Sanders SJ, Murtha MT, Gupta AR, Murdoch JD, Raubeson MJ, Willsey AJ, Ercan-Sencicek AG, DiLullo NM, Parikshak NN, Stein JL, Walker MF, Ober GT, Teran NA, Song Y, El-Fishawy P, Murtha RC, Choi M, Overton JD, Bjornson RD, Carriero NJ, Meyer KA, Bilguvar K, Mane SM, Sestan N, Lifton RP, Günel M, Roeder K, Geschwind DH, Devlin B, State MW. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. April 5, 2012. Nature.

O’Roak BJ, Vives L, Girirajan S, Karakoc E, Krumm N, Coe BP, Levy R, Ko A, Lee C, Smith JD, Turner EH, Stanaway IB, Vernot B, Malig M, Baker C, Reilly B, Akey JM, Borenstein E, Rieder MJ, Nickerson DA, Bernier R, Shendure J, Eichler EE. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. April 5, 2012.

Neale BM, Kou Y, Liu L, Ma’ayan A, Samocha KE, Sabo A, Lin CF, Stevens C, Wang LS, Makarov V, Polak P, Yoon S, Maguire J, Crawford EL, Campbell NG, Geller ET, Valladares O, Schafer C, Liu H, Zhao T, Cai G, Lihm J, Dannenfelser R, Jabado O, Peralta Z, Nagaswamy U, Muzny D, Reid JG, Newsham I, Wu Y, Lewis L, Han Y, Voight BF, Lim E, Rossin E, Kirby A, Flannick J, Fromer M, Shair K, Fennell T, Garimella K, Banks E, Poplin R, Gabriel S, DePristo M, Wimbish JR, Boone BE, Levy SE, Betancur C, Sunyaev S, Boerwinkle E, Buxbaum JD, Cook EH, Devlin B, Gibbs RA, Roeder K, Schellenberg GD, Sutcliffe JS, Daly MJ. Patterns and rates of exonic de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. April 5, 2012.

###

The mission of the NIMH is to transform the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses through basic and clinical research, paving the way for prevention, recovery and cure. For more information, visit the NIMH website.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit the NIH website.

Labels:

autism,

ceus for nurses,

genes

April 06, 2012

Antipsychotic drug may be helpful treatment for anorexia nervosa

Mouse model of anorexia offers opportunity to study drugs effective for disorder

Low doses of a commonly used atypical antipsychotic drug improved survival in a mouse model of anorexia nervosa, University of Chicago researchers report this month. The result offers promise for a common and occasionally fatal eating disorder that currently lacks approved drugs for treatment.

Mice treated with small doses of the drug olanzapine were more likely to maintain their weight when given an exercise wheel and restricted food access, conditions that produce activity-based anorexia (ABA) in animals. The antidepressant fluoxetine, commonly prescribed off-label for anorexic patients, did not improve survival in the experiment.

"We found over and over again that olanzapine was effective in harsher conditions, less harsh conditions, adolescents, adults — it consistently worked," said the paper's first author Stephanie Klenotich, graduate student in the Committee on Neurobiology at the University of Chicago Biological Sciences.

The study, published in Neuropsychopharmacology, was the product of a rare collaboration between laboratory scientists and clinicians seeking new treatment options for anorexia nervosa. As many as one percent of American women will suffer from anorexia nervosa during their lifetime, but only one-third of those people will receive treatment.

Patients with anorexia are often prescribed off-label use of drugs designed for other psychiatric conditions, but few studies have tested the drugs' effectiveness in animal models.

"Anorexia nervosa is the most deadly psychiatric disorder, and yet no approved pharmacological treatments exist," said Stephanie Dulawa, PhD, assistant professor of Psychiatry & Behavioral Neuroscience at the University of Chicago Medicine and senior author of the study. "One wonders why there isn't more basic science work being done to better understand the mechanisms and to identify novel pharmacological treatments."

One challenge is finding a medication that patients with anorexia nervosa will agree to take regularly, said co-author Daniel Le Grange, PhD, professor of Psychiatry & Behavioral Neuroscience and director of the Eating Disorders Clinic at the University of Chicago Medicine. Drugs that directly cause weight gain or carry strong sedative side effects are often rejected by patients.

"Patients are almost uniformly very skeptical and very reluctant to take any medication that could lower their resolve to refrain from eating," Le Grange said. "There are long-standing resistances, and I think researchers and clinicians have been very reluctant to embark on that course, since it's just littered with obstacles."

Both fluoxetine and olanzapine have been tried clinically to supplement interventions such as family-based treatment and cognitive-behavioral therapy. But their direct effect on anorexia nervosa behavior — in humans or animals — is lacking in sufficient data.

To test the effectiveness of these drugs in laboratory mice, Klenotich adapted the ABA protocol from previously published rat studies: Mice given 24-hour access to a running wheel but only six hours a day of food access become hyperactive, eat less and rapidly lose weight, with a 25 percent reduction from baseline considered to be the "drop-out" survival point.

In Klenotich's study, mice were pretreated with fluoxetine, olanzapine or saline before starting the ABA protocol, and treatment continued throughout the ABA period. Researchers then measured how many mice in each group reached the drop-out point for weight loss over 14 days of food restriction and exercise wheel access. Treatment with the antipsychotic olanzapine significantly increased survival over the control group, while fluoxetine treatment produced no significant effects on survival.

Importantly, a low dose of olanzapine did not decrease overall running activity in the mice, indicating that sedative effects of the drug were minimal. In future experiments, the researchers hope to use different drugs and genetic methods to determine exactly how olanzapine is effective against symptoms of anorexia nervosa, perhaps pointing toward a better drug without the negative image or side effects of an antipsychotic.

"We can dissect the effect of olanzapine and hopefully identify the mechanisms of action, and identify what receptor systems we want to target," Klenotich said. "Hopefully, we can develop a newer drug that we can aim towards the eating disorders clinic as an anorexic-specific drug that might be a little more acceptable to patients."

The study offers support for the clinical use of olanzapine, for which clinical trials are already under way to test in patients. Le Grange said the development of a pharmacological variant that more selectively treats anorexia nervosa could be a helpful way to avoid the "stigma" of taking an antipsychotic while giving clinicians an additional tool for helping patients.

"I think the clinical field is certainly very ready for something that is going to make a difference," Le Grange said. "I'm not saying there's a 'magic pill' for anorexia nervosa, but we have been lacking any pharmacological agent that clearly contributes to the recovery of our patients. Many parents and many clinicians are looking for that, because it would make our job so much easier if there was something that could turn symptoms around and speed up recovery."

Additionally, the study demonstrated the innovative experimental design and translational results that can come from a collaboration of laboratory and clinical experts.

"We don't talk to one another often enough in basic science and clinical science," Le Grange said. "More of that would be helpful for clinicians to understand the neurobiology of this disease. I'm very excited about the way this project is going, and I think it's going to be clinically very informative."

###

The paper, "Olanzapine, but not fluoxetine, treatment increases survival in activity-based anorexia in mice," was published online March 7 by Neuropsychopharmacology (doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.7). In addition to Klenotich, Dulawa and Le Grange, authors include Mariel Seiglie and Priya Dugad of the University of Chicago and Matthew S. McMurray and Jamie Roitman of the University of Illinois at Chicago. Funding for the research was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health.

For more news from the University of Chicago Medical Center, follow us on Twitter at @UChicagoMed, or visit our Facebook page at facebook.com/UChicagoMed, our research blog at sciencelife.uchospitals.edu, or our newsroom at uchospitals.edu/news. counselor ceus

Labels:

counselor ceus,

mental health

April 04, 2012

How stress influences disease: Carnegie Mellon study reveals inflammation as the culprit

PITTSBURGH—Stress wreaks havoc on the mind and body. For example, psychological stress is associated with greater risk for depression, heart disease and infectious diseases. But, until now, it has not been clear exactly how stress influences disease and health.

A research team led by Carnegie Mellon University's Sheldon Cohen has found that chronic psychological stress is associated with the body losing its ability to regulate the inflammatory response. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the research shows for the first time that the effects of psychological stress on the body's ability to regulate inflammation can promote the development and progression of disease continuing education for social workers

"Inflammation is partly regulated by the hormone cortisol and when cortisol is not allowed to serve this function, inflammation can get out of control," said Cohen, the Robert E. Doherty Professor of Psychology within CMU's Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

Cohen argued that prolonged stress alters the effectiveness of cortisol to regulate the inflammatory response because it decreases tissue sensitivity to the hormone. Specifically, immune cells become insensitive to cortisol's regulatory effect. In turn, runaway inflammation is thought to promote the development and progression of many diseases.

Cohen, whose groundbreaking early work showed that people suffering from psychological stress are more susceptible to developing common colds, used the common cold as the model for testing his theory. With the common cold, symptoms are not caused by the virus — they are instead a "side effect" of the inflammatory response that is triggered as part of the body's effort to fight infection. The greater the body's inflammatory response to the virus, the greater is the likelihood of experiencing the symptoms of a cold.